Chapter One Concord, Massachusetts Summer 1836 I know that Mr. Emerson is expecting me. It was he, after all, who invited me here. And yet, as I approach the front door of his grand white home, I feel a twinge of nerves. I pause, staring up at the house, an imposing structure set back from the Cambridge Turnpike, hemmed by a fence, the columned porticoes and rolling green lawns lending the place a simple, stately elegance. “Bush” is what Mr. Emerson called the estate in his letters, when he wrote to invite me from Cambridge out to the country for a week’s visit.

He’d read my newspaper tribute, Mr. Emerson explained, to his beloved brother Charles, so recently deceased of tuberculosis. He’d found that my words had touched his heart, providing some small balm to the pain of the untimely loss. I was a young writer of great promise, Mr. Emerson declared, his fine cursive filling the front and back of the page. As one of New England’s most established lecturers and perhaps its most prolific writer, he, Mr. Ralph Waldo Emerson, took great pride in being able to support individuals like me. Even women, his words implied, though he had not stated that outright. But really, he hastened to add, the primary purpose of the visit was to provide companionship for his wife, Mrs. Lidian Emerson, now in the final months of her confinement before the expected arrival of their first child, and barely able to leave her bed.

“He’s collecting friends and thinkers to his side,” Eliza Peabody had told me, when she welcomed me into her Boston parlor for tea on the eve of my planned departure. Eliza, my friend of several years, and I had gravitated toward each other as two of the only young ladies in the Boston and Cambridge writing circles who shared the twin stains on our reputations of being unwed

and wishing to work as published writers. We had an audacity to us that frightened many, an independence of spirit and circumstance that made us not a little bit threatening to some of the men who wrote about freedom and lectured about liberty. An independence that allowed me to accept an invitation such as this one from Mr. Emerson, to stay as his houseguest in the country.

Eliza was in a position to tell me what I might expect from a visit at Emerson’s estate, as she herself had made the very same three-hour journey by stagecoach from Boston to Concord on more than one occasion to accept a similar invitation—or was it a summons?— to the Emerson home.

“He knows of you, Margaret. Knows your reputation, evidently even knows some of your writing,” Eliza said, stirring a pinch of sugar into her tea as she held me with her intense, inquisitive gaze. I did my best to bite back the flattered smile that pulled on my lips. To think, my work had been read—and enjoyed—by a man such as Ralph Waldo Emerson. Certainly there were many who found my work and my passions unladylike, even unnatural. But not Mr. Emerson, it seemed.

Eliza went on: “Sophia and I were with the Emersons out at Bush in the spring.” While Eliza was a celebrated wit and lady of letters, her sister Sophia was known to excel at painting. “It promises to be interesting, my dear, to say the least. A chance to glimpse the great Sage of Concord at home.”

And now here I stand, clutching my cloth bag and gazing at the front door of Mr. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s home. I glance down at my dress, a simple poplin of dove gray, a cream-colored kerchief tied modestly around my neck. I pat the skirt and then raise my gloved hands to make certain that my chestnut bun is tidy, the curls bobbing down the nape of my neck, giving myself one final prink before I knock.

I’m expecting a servant of some sort, perhaps a housekeeper or cook, but the man who greets me at the door is none other than Mr. Ralph Waldo Emerson himself—I know his famous face. “Oh, yes, Mr. Emerson?” I shift my bag from one hand to the other, forcing a bright tone even as I feel my cheeks grow warm. “Hello.”

Mr. Emerson looks at me, one corner of his mouth tilting upward, the hint of a half smile, and then he extends a hand in greeting. “And this must be the famous Margaret Fuller of Cambridge at my doorstep?”

I take his outstretched hand and let out a puff of breath that sounds like a warble. I’m struck by the deep timbre of his voice, and by his informal manner—I hadn’t expected either. Already he’s caught me back on my heels, so I square my shoulders and summon a casual smile as I reply: “I don’t know about

famous, but I

am Margaret Fuller indeed.”

His smile grows from partial to full as his blue-gray eyes catch a lively glimmer. And then he sweeps his arm up, performing a slightly theatrical bow. “Welcome to Concord. Please, Miss Fuller, won’t you come inside?”

I accept his welcome and step past him, out of the warm summer afternoon and into the cool and airy quiet of the Emerson home. The foyer is bright and high ceilinged, with a gracious stairway and wooden banister before us and spacious rooms off to each side. I stand still as my host asks after my journey and I tell him it went smoothly. There is neither sight nor sound of any other person in the home, which lends the handsome place an almost temple-like tranquillity. I clutch my valise as Mr. Emerson ushers me across the front hall and into a room lined with books. His study, I suppose. A large mahogany desk occupies pride of place, topped with a tidy stack of papers and a pen tipped into a dish shaped like a bird. Beside it sits a half-filled inkwell. The room smells of books and firewood.

Mr. Emerson stands beside his desk. “What refreshment can I offer you, Miss Fuller, after your hours-long journey? Some tea? Coffee? Water? Ah, or we do have some nice cider which our dear handyman has pressed for us.”

“Water would be fine,” I answer. As he pours us two cups from a pitcher on a nearby side table, I take the opportunity to subtly study his appearance. Ralph Waldo Emerson is tall and slender, dressed in a tidy suit with a cravat that hugs high and tight around his neck. I know from his reputation as a great speaker and writer that Mr. Emerson is a few years older than me, thirty-three to my twenty-six. Nevertheless, he has an undeniably youthful vitality about him; perhaps someone so filled with deep thoughts and ideas cannot help but overspill with an uncoiled sort of energy.

“Thank you.” I accept the water from his hand and take a sip. Our eyes lock for a moment and I allow my stare to linger in his cool gaze, before I remind myself to look away. I take another sip, my throat feeling dry, and I tell myself it’s because of the three hours on the turnpike.

“Sit, please.” Emerson gestures to a sofa of red velvet across from his desk, then he crosses the room to shut the door. I take note of the fact that I have not sat alone in a room with a man since my father’s death. I blink, glancing down toward my hands in my lap. But Mr. Emerson does not seem to find this closeted state of affairs unusual in the least, as he takes his own seat in a rocking chair behind his desk.

“Well, Miss Fuller, thank you for coming all this way.” He reaches for the nearby poker and jostles the logs in the hearth, just a small blaze given the warmth of the summer afternoon.

I nod. “Thank you for your gracious invitation.”

“It has been a matter of great interest to me for some time . . . meeting you.”

I can barely mask my surprise; I had supposed the chief purpose of my visit was to offer company to Mrs. Emerson. I reply only, “Oh?”

“The Most Well-Read Woman in America,” he says with a flourish of his long-fingered hands, then he sets his gaze back on me. “That’s what they call you, if I’m not mistaken?”

“Person,” I reply, my voice quiet but certainly audible.

Emerson tilts his head, eyeing me with a bemused expression. “Pardon?”

“Person,” I state again, this time just slightly louder. “What I’ve been called is ‘the Most Well-Read

Person in America.’ ” Almost as soon as I’ve said it I regret doing so—the importance of first impressions and modesty being what they are. Particularly in a lady, and a junior one at that. Mother is always reminding me of this, chiding me when my pride or boldness seems too much. And Father did the same.

Margaret, my girl, you are the Much that always wants More. The thought of Father—his words, his memories—it all causes my vision to swim for a moment, until I remind myself not to get lost in the pull of these daydreams.

Mr. Emerson is looking at me most intently. I sit up taller in my seat. My host offers me half a smirk, and then he speaks again: “Won’t you please tell me how it is that you are so well educated?” He tents his long fingers, looking at me over their tips. “Where was your formal schooling?”

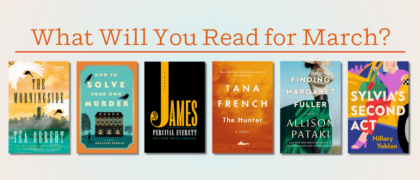

Copyright © 2024 by Allison Pataki. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.