Dear Librarians,

When I was wrongfully arrested for a murder I didn’t commit at age 19 and thrown into the New Orleans jail to stand trial, an older man who had already been convicted and sentenced to death told me that if I had any hope of saving myself, I would need to teach myself the law.

At the time, I had a ninth-grade education. Reading had never come easy to me for two reasons. First, I got started very late. As a kid, my sister and I spent our early years on the run with a mother trying to escape an abusive boyfriend. The first time I remember attending school regularly was in the second grade. I could understand and learn just fine by listening, but the letters on the page were foreign to me.

Second, I was legally blind in one eye and didn’t know it. When I was little, my older brothers were smashing glass bottles in the projects, and a piece of one kicked up and cut my cornea. If I’d been treated then, I might’ve recovered my sight. But the injury was never corrected, and I lost the use of that eye. As a kid, you don’t realize you’re experiencing the world differently. It wasn’t until I was sixteen and sent to Job Corps that a nurse discovered my disability.

So there I was in jail, nineteen years old and fighting for my life, and the one thing I had do to try to save myself was read.

The jail didn’t have any books, so I started with The Bible. Soon, I filed my first motion—A Motion for a Law Book—and when a judge gave me a code of criminal procedure, I began my journey with the law.

Despite my efforts, I was wrongly convicted, and at age 24, I was sent to Angola prison to serve a sentence of life without parole.

Once there, I started asking myself: What do I believe in? What purpose is my life going to serve? I found answers in the prison library.

For the first time, I was able to read novels written by people who had survived worse than me and lived to share their wisdom. From Kunta Kinte in Roots, I learned that America could put chains on my body and the bodies of my ancestors—but never on my mind. From Dr. Larch in The Cider House Rules, I learned to be of use—that I could only help myself by first helping others. From Viktor Frankl in Man’s Search for Meaning, I learned how to withstand despair—that I needed to hold onto a hope beyond myself.

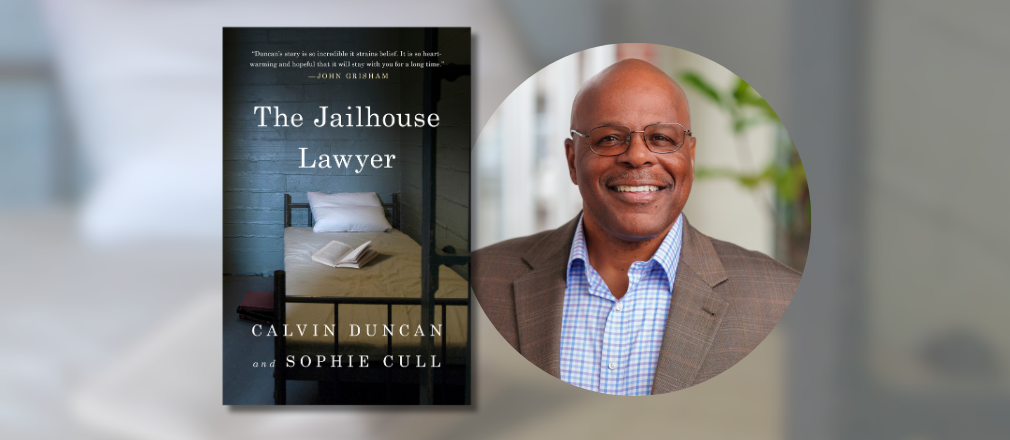

Over the next 23 years, books became my lifeline, a means of survival, and a way to offer something to others searching for answers of their own. I hope I can pay it forward with The Jailhouse Lawyer; that my book can show people, inside prison and out, how to hold onto their convictions and fight for what’s right, even when the odds are against us.

Thank you for reading my story, and for the work you do every day to share books with a world that needs more hope.

-Calvin