Q: Libraries are mentioned several times in Murderland—going back decades. Do you remember one of the first books you ever checked out from the library?

A: I have such vivid memories of the children’s room of the Seattle Public Library. I loved it there. I think my mom checked out my books when I was little, so I don’t remember which book was the first. She was a teacher (kindergarten and first grade), so she knew all the best ones!

I do recall crouching on the rug in the main area of the children’s reading room and closely studying the pictures in Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, Margaret Wise Brown’s The Sailor Dog, and those incredible Robert McCloskey books, especially Blueberries for Sal. That book was about his daughter in Maine, of course, but when I was little, I thought it was about the Northwest, because everything in the illustrations looked so similar—evergreen trees, clams on the beach, berry-picking. Although in our case it was blackberries, not blueberries.

Q: Do you have a favorite memory of going to the library?

A: When we were in junior high, my friend Susie and I were allowed to take the bus to downtown Seattle by ourselves to go to the main library, and we felt very grown-up. We were reading a lot of the same books and passing them back and forth, the Narnia books, Joan Aiken and her Wolves chronicles, and Laura Ingalls Wilder (of course). The Lord of the Rings. It was our special place.

Q: What role did libraries have in your writing process, if any, for Murderland?

A: There wouldn’t be a Murderland without libraries, and that goes for virtually every other book I’ve written. I started during Covid when everything was closed, but I was able to go to Seattle and Tacoma in 2022 and again the following year. The Seattle Public Library has amazing resources in its Seattle Room, yards of filing cabinets with collections of pamphlets, brochures, photographs, maps, newspaper clippings, and records of city and state departments. A lot of the stuff I used in writing about the Mercer Island floating bridge came from that collection.

At the Tacoma Public Library, the Northwest Room—their rare books and archives collection—was invaluable. The first time I went there, I learned from the archivist that they were in the midst of cataloguing a major collection of ASARCO materials—files and photos from the American Smelting and Refining Company donated by the EPA after the Tacoma smelter shut down in the 1980s and the corporation bailed. I suspect that the company had cleansed their files to some extent, but there were still some eye-opening things, including angry union flyers about a fatal electrocution at the plant and a “Death List” of workers, sometimes fairly young, who died of lung cancer, probably due to arsenic exposure.

The Northwest Room also has fantastic clipping files from previous decades, about crime and violence in Tacoma. I could have spent a long time there, but I was lucky to get the opportunities I did, since the building, a beautiful old Carnegie library, was under renovation (still is). I hope I get a chance to go back sometime.

Q: There is an autobiographical element to Murderland. In what ways did your story inspire you to write this book?

A: There were certain memories that I was struggling to understand, like the story about the man who lived down the street from us who blew up his house and killed himself. Back in the 1960s and ’70s, we never talked about things like that, or about the war in Vietnam, or assassinations, or violence. As a result, I think writing became for me a way of trying to figure things out. Being able to put events in the context of a broader history was important for me, and I hope that the personal/historical juxtaposition gives readers a feeling of what it was like to live through that tumultuous time.

Q: Sense of place is a major theme in Murderland. Has the library ever been a part of that experience for you as a person? As a writer?

A: Absolutely. I think the reason why I revere libraries and have always felt safe in them is because they offered a way out of a stifling way of life. My family’s involvement in Christian Science meant that it was hard for me to understand things that were normal for other kids, like medical care (we were supposed to pray when we were sick and never went to doctors). So libraries pretty quickly became an essential way of comprehending the wider world, and they offered a respite, a quiet, private place to think my own thoughts.

I think that’s why I ended up working parttime in libraries all the way through high school, university, and grad school. I was working after school at the Mercer Island Public Library one day when I came across John Hersey’s book Hiroshima. I was supposed to be “shelf reading” and instead I sat down in the corner and read it. I was just stunned by it. I may not have been the best employee, but it was kind of a life-altering experience.

Q: In Murderland, there is a poem that you wrote for a Creative Writing class in college. When did you take the leap to writing books and, ultimately, becoming an author? Have you always been a writer?

A: My mom helped me to make books when I was eight or nine, tying pictures together with yarn—early self-publishing. In junior high, my friend Susie and I were writing a fantasy novel. I think she still has parts of it.

So I was always writing. When I went to college, I got a little scholarship to write a novel. It was pretty terrible, but I loved being able to do it. By then I had fallen hard for poetry and was already interested in nonfiction. I was blown away by reading Susan Sheehan’s three-part article in The New Yorker about a woman who had schizophrenia. It was just riveting. She won a Pulitzer in 1983 for the book, Is There No Place on Earth for Me?

Q: What’s something you hope readers will take away from Murderland?

A: I hope readers will feel in Murderland something that’s also present in Prairie Fires, which is a sense of how historical movements shape lives. In Prairie Fires, I was telling a story about Laura Ingalls Wilder who had become so celebrated and mythologized (largely on television) that she was transformed into a legend. She was so beloved that a lot of mythic and sometimes wrong-headed assumptions had grown attached to her, like barnacles, obscuring who she really was—her complexity as a person—and how she encompassed so many of the contradictions of American farming.

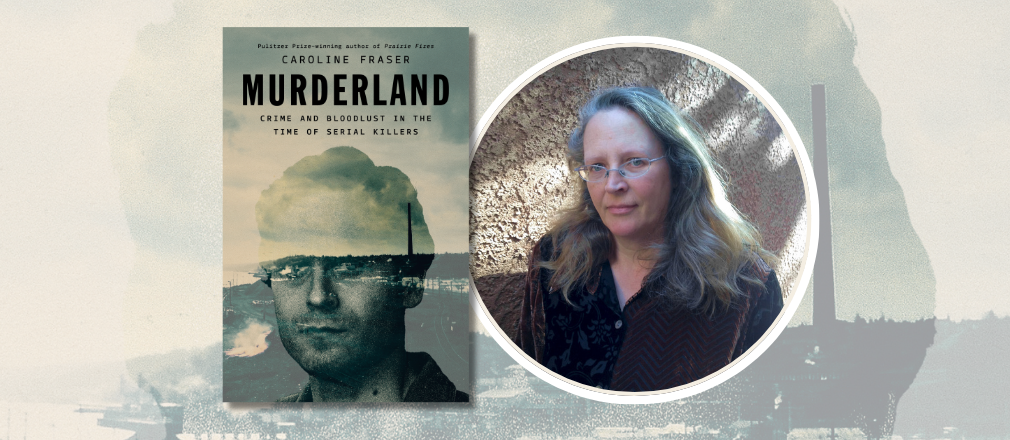

In Murderland, I’m looking at another much-mythologized figure, Ted Bundy, whose horrific exploits have been exaggerated, even glamorized in some ways, in movies and on television. Again, I wanted to tell the real story, not as a who-done-it, but as a way of seeing him and others like him as part of a pattern of violent crime in this country. The period when he was active was not only one of the most violent periods in American history but also a time when industrialized pollution was allowed to wreak havoc on cities across the West.

Murderland tries to grapple with an explanation for serial killing: Why were the 1970s through the 1990s the worst period for violent crime? Why were there more serial killers then than there are now? Telling Bundy’s story against that backdrop, painting a portrait of the power concentrated in mining, smelting, and leaded gas, we can see that corporations themselves were predators, skilled at serial lying and indifferent to the consequences of their actions. The fact that lead exposure in children leads to higher crime rates is well understood, but we’ve never reckoned with it publicly.

These questions are especially relevant today, since we’re facing extreme attacks on the environmental laws that closed the smelters down and cleaned up our air, water, and soil. Without those laws, we could be returning to conditions that produce more crime.

Q: If you could say one thing to librarians right now, what would it be?

A: Keep fighting the good fight. Stay strong. I was so dismayed to see the cuts to the Institute of Museum and Library Services. We need libraries more than ever, for all the services they provide, and we need librarians to keep history and literature and facts accessible. The book banning and censorship and attacks on free speech will collapse eventually, as they always do. But it may get worse before it gets better.