Dear Librarians,

When I first began working at my town’s public library, I loved celebrating Banned Books Week. This would have been in 2010, years before I’d ever watched a book challenge play out in my own community. I remember how another librarian and I would sort through the documents provided by the ALA, marveling at how wild it was to see things like The Hunger Games and Twilight on the list. What were people thinking? we’d wonder. We’d make displays and wear our I read banned books socks and pins and we would say it was our favorite week in the library.

It was nearly ten years before I understood the weight of that week.

I had a daughter by then. She was in second grade. She loved Legos and skiing and she also happened to be transgender, a fact my husband and I had taken some three years to understand and accept. Her social transition–changing her name and pronouns, letting her hair grow out and giving her the dresses she’d wanted for years–had made a layer of rage she lived with drop off like the heaviest of capes. In its place, a light came on inside of her.

But her transition also caused our town to erupt in vicious school board battles about her rights. Meanwhile, my daughter endured constant bullying as she struggled to get her peers to understand who she was and why she’d changed her name and pronouns.

“Why can’t the teachers just read a book so kids understand?” she kept asking me.

I kept asking the school the same question. It would be months before I got my answer: books with characters like my daughter had been banned from classroom use. The decision had been made quietly, at a private school board meeting, with no public input and no public notes.

For the first time, I understood the impact of a book ban. I understood that it blocked my daughter from any hope of belonging in that community.

I’ve since left that town for a nearby city, and early in my daughter’s fourth grade year, she decided she wanted to come out to her new class. Terrified of bullying, I reached out to her teacher for support. “No problem!” she said. “I’ll talk with her and we’ll make a plan!”

The plan was simple: read a book. And it worked. My daughter came out, a few classmates remarked that they had transgender people in their family, and after that, no one ever said one more word to my daughter about her gender.

I work as a high school librarian now. I still celebrate Banned Books Week every year, but it’s different, because I actually understand it. “Did you notice that most of these bans are for books with Black or LGBTQ+ characters?” I ask the students. I tell them to remember that these statistics are only a small fraction of the story; I tell them that most book bans are insidious, as they were in my former town. “What do you think happens when stories about particular identities are blocked?” I ask them.

They don’t always answer, but last year, a student left us a note before she graduated. She wrote that she was so thankful to see the books–especially the children’s books–become more inclusive. “What we have here is incredible compared to what I had access to when I was younger,” she wrote.

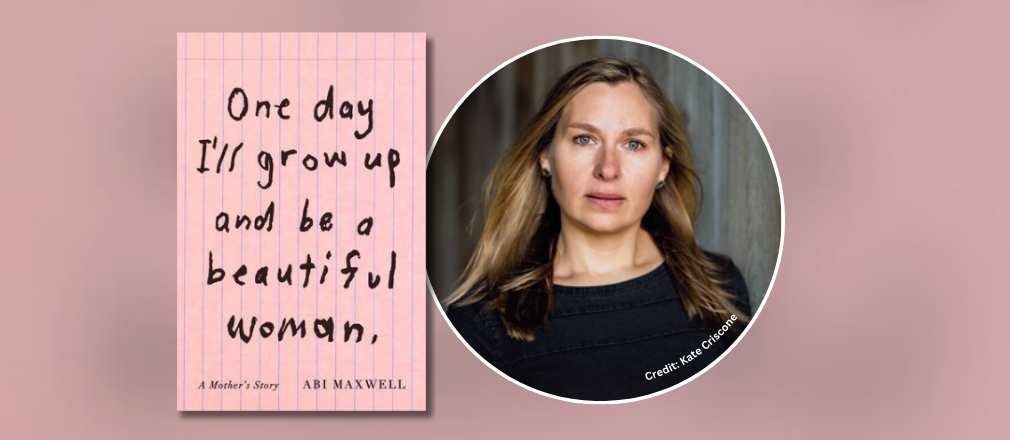

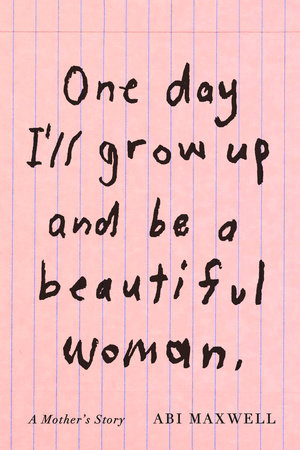

I cherish that note, not because it compliments the collection we have built, but because I know that when that student found books with people like her in our stacks, it told her that she belonged in our community. I hope that my memoir, One Day I’ll Grow Up and Be a Beautiful Woman, will do the same for countless families like mine, and I hope it will provide us all with a window into the deep harm of book bans.

With courage and so much gratitude,

Abi Maxwell