Dear Librarians,

Thank you.

My life, my entire self, wouldn’t be possible without you. From the time I was very young, my mother took me to libraries. I clearly remember the North Park Branch of the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library, where my mother and I would go on Saturday mornings. When I was old enough, I’d ride my bike there each week. On my ride home, the bike basket would be filled with books. I was an only child, shy, sometimes withdrawn, hesitant to make friends, wary of speaking to anyone outside my family—except at the library, where I found solace, comfort, and acceptance. The library was a place where entire worlds opened before me and my imagination took flight.

In my youth, I had obsessions that seem odd in retrospect, but the librarians never objected. One obsession was with Napoleon and his family. In home economics class in sixth grade (in my school, girls were assigned to take home economics and boys took shop, which meant carpentry, regardless of our individual interests), we girls were asked to write reports on some aspect of baby care, based on a baby we actually knew, such as a sibling, or a cousin. I had no siblings, I had no baby cousins. I knew no babies.

What to do? One baby I did feel I knew personally, from my reading, was Napoleon’s son, called the King of Rome. I chose to write a report about his toilet training, and my favorite librarian helped me to find the extensive materials available on exactly this topic. My teacher was, I recall, somewhat perplexed, but she gave me an A on the report, which I was able to show the librarian the next week. How I wish I could remember this librarian’s name, so that I could tell her how much her understanding meant to me, how she gave me trust in my ability to think and create outside the norm.

As I grew older, my initial reaction to every question or difficulty I faced was to go to the library to research it. Only after doing this could I make a decision—after the library, and my librarian-guides, had given me the knowledge I needed. It’s not a coincidence that I decided to focus on writing historical fiction, a genre that requires me to spend hours and hours at the places where I feel most confident, most encouraged, and most myself: libraries.

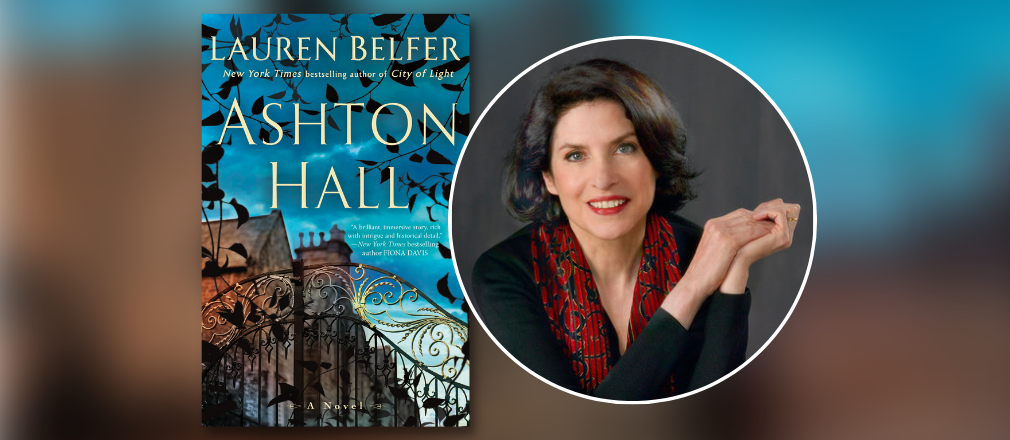

ASHTON HALL, my most recent novel, is my first set entirely in the present, but through the unfolding of the story, I wanted to explore how we as individuals go about recreating the past. This process feels very personal to me, because it developed from my own experiences researching my family’s history, visiting the town they came from in Europe, finding their names in old business directories, studying birth and death records.

As I researched my family’s history, I began to wonder what scholars of the future might find if they researched me. What evidence would they have to work from? My credit card bills. Checking account statements. Tax returns. Charitable donations, showing what I valued.

Most importantly, I realized, my life would be revealed by a list of all the books I’ve checked out of libraries. This comprehensive listing would disclose almost everything about me—my hopes, dreams, challenges, interests; what I’ve enjoyed or worried about.

I came to understand that such a list would do the same for the sixteenth-century fictional characters in my novel.

And so I created a library and an accompanying library register for my fictional stately home, Ashton Hall. Determined to fill Ashton Hall’s fictional library with real volumes, I did extensive research into medieval and early-modern books in England. I figured out what each member of the household would read—or, more correctly, the characters informed me of the books they wanted to read. Through interlibrary loan, my local librarian gathered materials for me from far-flung institutions around the country.

During the course of my research, I read that upper-class women often served their families and communities as informal physicians and that they made remedies from herbs. Because of this, I immersed myself in herbal medicine. One crucial book I needed to examine was the Herball of John Gerard, originally published in 1597. I was thrilled to discover that a library in New York City possessed a copy of one of the early editions. The librarians there seemed equally thrilled when I requested an opportunity to examine it.

I vividly remember the day I went to the library to see John Gerard’s Herball … I waited in the conservation room. Soon, the special collections librarian carefully wheeled from the elevator a cart holding the huge book, large-format and well over a thousand pages long. With assistance from the conservator and the head librarian, she shifted it to the multi-part book cradle that had been prepared for it on a table. While I leafed through the book, the librarians rearranged the cradle to provide maximum support for the binding. They asked me about my research.

And as we together examined this astonishing book, over four hundred years old, filled with gorgeous illustrations of plants, once again I knew that librarians were with me, as they had been since I was young, helping me, encouraging me … standing, always, beside me.

With deepest gratitude,

Lauren Belfer