1

A Winter Leveret

Siberians name hares by the time of their birth:

nastovik (born in March, when snow is covered with crust),

letnik (born in summer),

listopadnik (born in the fall, when leaves fall from trees).

—A. A. Cherkassov,

Notes of an East Siberian Hunter, 1865

Standing by the back door, readying for a long walk, I heard a dog barking, followed by the sound of a man shouting. I jammed my feet into my boots and walked across the gravel to the wooden gate to look for the cause of the disturbance. There was no reason for a dog to be nearby. The barn where I lived stood alone in a broad expanse of arable farmland, quartered by streams and hedgerows and interspersed with stands of woodland. I had grown up with stories of poachers cutting locks and forcing open gates to drive onto the farmers’ fields and into the woods, hunting deer and rabbits or setting their dogs to chase hares. More benignly, dogs had been known to bolt from their owners walking down the lanes, in pursuit of a rabbit or simply drawn by the open spaces, scattering sheep or disturbing nesting birds in the process. A zealous dog, panting from the chase, had jumped over the wall into my garden once the previous year, lunging at nothing and sawing the air with its tail in a playful manner before bounding up and off and away. But such incidents were rare, and I was curious to know what was happening.

I leant on the gate and scanned the field, which rose in a gentle incline towards the horizon and then dropped out of sight. The sky was gunmetal grey. I ran my gaze along the hedgerows, over the expanses of bare stubble and lingering patches of slowly dissolving snow, and towards the dark silhouette of the nearest wood. Whatever dog had been on the loose was no longer visible. The wind cut at my cheeks with an icy edge. The white fog of my breath was whipped away. I fumbled in my pocket for my gloves, pulled my coat closer around me and set off for a walk.

The path I took was a short, unpaved track leading along the edge of a cornfield and emerging into a narrow country lane flanked with tall hedges overflowing with bramble and snowberry. The track, formed of two strips of hard-packed earth, was solid enough for a car to pass but pocked with potholes and puddles. I crested the skyline, deep in my thoughts, and began to walk down the slight slope towards the lane, when I was brought up short by a tiny creature facing me on the grass strip running down the track’s centre. I stopped abruptly.

Leveret. The word surfaced in my mind, even though I had never seen a young hare before.

The animal, no longer than the width of my palm, lay on its stomach with its eyes open and its short, silky ears held tightly against its back. Its fur was dark brown, thick and choppy, and grew in delicate curls along its spine. Long, pale guard hairs and whiskers stood out from its body and glowed in the weak sun, creating a corona of light around its rump and muzzle. Set against the bare earth and dry grass it was hard to tell where its fur ended and the ground began. It blended into the dead winter landscape so completely that, but for the rapid rise and fall of its flanks, I would have mistaken it for a stone. Its forepaws were pressed tightly together, fringed in fur the colour of bone and overlapping as if for comfort. Its jet-black eyes were encircled with a thick, uneven band of creamy fur. High on its forehead was a distinct white mark that stood out like a minute dribble of paint. It did not stir as I came into view, but studied the ground in front of it, unmoving.

Leveret.

The gaping mouths of rabbit burrows beneath trees and banks, and the flash of their inhabitants’ white cotton-ball tails, were familiar sights from my childhood. But hares were rare and secretive, only ever glimpsed from afar, in flight. To see a leveret lying out in the open—or at all—was very surprising. The most likely explanation for its exposed position was that it had been chased, or picked up and dropped, by the dog I’d heard, and had ended up lost on the track.

I considered the options. I could leave the leveret where it was, hoping that it would find its way back into cover and be retrieved by its mother before it was found by a predator or crushed by the wheels of a passing car. I could pick it up and tuck it into the long grass, with the risk—I thought—that its mother might not be able to find it since it could have been carried or chased some distance from its original hiding place, or that she might reject it.

As a child, I had loved lambing season and used to spend time on a nearby farm. I had seen the way a mother sheep, or ewe, could pick out her young from a field of lambs by its smell alone. Any other lamb that approached her, or tried to drink her milk, would be firmly pushed away. I remembered watching a farmer persuade a ewe whose own lamb had died to suckle an orphan from another mother by wrapping it in the skinned pelt of her dead lamb. Only if the orphan smelled sufficiently like the lamb she had lost would the foster mother raise it. Transferring my alien scent onto the leveret by picking it up—even if just to move it by a few feet—might be to kill it with kindness.

It seemed impossible that the fragile animal at my feet could survive by itself in a landscape teeming with dangers, including foxes and the hawks I often saw hovering close to the ground before closing their wings and dropping like stones upon their prey. The leveret had no protection against these earth-dwelling or sky-borne killers. However, I knew that human interference could do more harm than good, so I decided that I had better let nature take its course. I would leave the leveret where I had found it, in the hope that it would hurry into the long grass as soon as I had gone, and be reunited with its mother. I counted the number of fence posts so I could remember the spot and went on my way.

When I returned, four hours later, I had almost forgotten the leveret. But there it was, on the open track, exactly as I had left it. It lay without a scrap of cover, with buzzards wheeling in the sky above, keening mournfully like lost souls. I hesitated, considering the several hours of daylight that still remained. It seemed odd that the mother hare had not come back to reclaim her young, as I thought she surely would have done. I weighed the possibility that the leveret had been injured by the dog, or that its mother had been killed. In either case, if it did not move from the track, the chances that it would be hit by a car or attacked and eaten increased the longer it lay in the open.

Acting on instinct, and still uncertain about the right course of action, I decided that I would take the leveret home until nightfall, when I would return it to where I had found it. To avoid touching it with my hands, I gathered several handfuls of the dead grass fringing the track. I crouched down on the ground, half expecting it to dart away. It did not flinch. I placed one hand on either side of the leveret’s body, and lifted it carefully to my chest, wrapped in the grass, before walking the few hundred yards to my back door.

Once home, I placed the leveret anxiously on a countertop so I could examine it for injuries, wrapping it loosely in a new yellow dust cloth to continue to avoid directly touching its fur. To my relief, I could find no sign of bleeding or a wound. It pushed itself up on trembling front paws, each barely half the length of my little finger and as slender as a pencil, and sat unsteadily on its hindquarters, blinking, its nostrils flaring as if it were taking in its strange surroundings. The leveret looked even smaller in the house than it had on the track, dwarfed by any object designed for human purposes. But it seemed unafraid and made no attempt to run away from me. Its mouth was a tiny sooty line, situated on the underside of its rounded little head and curved down at both corners as if the leveret were already slightly disappointed by life. Its ebony eyes had the faintly milky, purple sheen of many newborn creatures. Its whiskers were short and stiff, while its hind legs bent at a sharp angle, its rear paws almost half as long as its body.

I rang a local conservationist, formerly a gamekeeper, to explain what had happened and ask for advice. He quickly dispelled my notion that I could return the leveret to the field. He told me that even if it could somehow find its mother, she would reject it, since it would now smell of humans despite my precautions. Moreover, he said that in decades of working on the land, he had never heard of anyone successfully raising a leveret. “You have to accept that it will probably die of hunger, or shock,” he said, speaking kindly but bluntly. “I’ve met people who have reared badgers and foxes, but hares cannot be domesticated.”

I felt embarrassed and worried. I had no intention of taming the hare, only of sheltering it, but it seemed that I had committed a bad error of judgement. I had taken a young animal from the wild—perhaps unnecessarily—without considering if and how I could care for it, and it would probably die as a result. My heart sank.

I grew up abroad with my parents, who worked overseas, and my three siblings. We returned to England during the holidays, to visit family, and my childhood summers were spent at our home in the countryside. My mother had an extraordinary way with animals, and I remember a succession of hedgehogs and baby jackdaws and even a greenfinch, rescued from the jaws of a crow, that she nursed back to health, to my delight. I loved those days, but as I finished school and later university, I set my face towards London and the world beyond.

The years that followed took me steadily away from the countryside. Life, and its beating heart, lay for me in the city, where I was drawn into the world of politics and foreign policy, working as a political adviser. I developed ideas and strategies for public figures, helped put their thoughts into words, and stood by them in the “war room” in a crisis, working with a close team of equally committed people. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, author of

The Little Prince, wrote that “there is no comradeship except through unity on the same rope, climbing towards the same peak,” and he might as well have been describing the single-mindedness that animated me and my colleagues. We used to joke that in another time, during a coup or revolution, when everyone else had fled, we would be the last to go down.

If I had an addiction, it was to the adrenaline rush of responding to events and crises, and to travel, which I often had to do at a few hours’ notice. I avoided fixed plans that would remove the flexibility to take a bag and go, and what I missed of holidays and family occasions I believed I gained in novel, unrepeatable experiences and exposure to parts of the world I might otherwise never have seen: glimpses of Bamako, Baghdad, Kabul, Algiers, Damascus, Ulaanbaatar, Tallinn, Sarajevo and Siem Reap. Working on the weekends and over holidays became second nature. It would have been cruel to keep a pet at home under these circumstances, and I lacked the mindset for it. I worked on international crises involving people, and seldom considered animals. My time was spent in offices, meeting rooms and airports. I would not have called myself a practical person. The last animal I had cared for was a white mouse named Napoleon I’d had when I was eight years old, and that had ended badly when the family cat overturned and opened his cage one day while I was at school, with predictable consequences.

When the centrifugal forces of the pandemic flung me home to the countryside and pinned me there, relief and awareness of my good fortune warred inside me with a deep restlessness and anxiety about the future. I struggled with the change of pace. A friend and colleague came with me when we shut our office. She and I maintained the strict rhythm of our working days and planned incessantly our return to the city. A baby hare had no place in any of the scenarios we had discussed or that I had envisaged for myself. On a solitary walk a few days previously, I had sat down on a rock by a stream that was little more than a rivulet, my boots squelching in the mud, the lifeless trees above me scarcely bleaker than my own thoughts, and indulged in miserable feelings about my own life slowing down to a commensurate trickle. And now—improbably—I stood over a wild creature that I would have to find a way to feed and keep alive.

The leveret waited patiently, oblivious to my thoughts. My friend, observing the scene, put my doubts into words. “Don’t take this the wrong way, but I’m not sure this is a good idea,” she ventured. “What will you do with it when you go back to London? Wouldn’t it be better if you gave it to someone else—someone who actually knows about animals?” I had been thinking the same thing, but as she spoke, I felt an inner stubbornness stirring.

I will work it out.

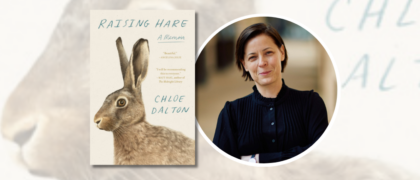

Copyright © 2025 by Chloe Dalton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.