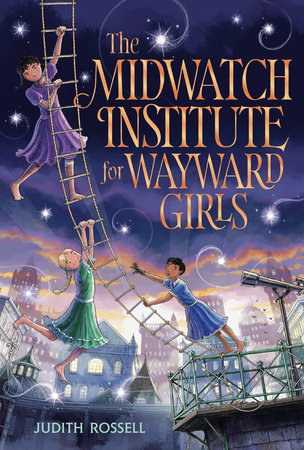

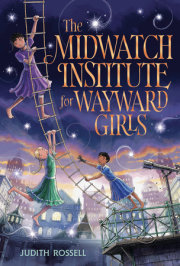

Chapter One

It was late afternoon when the little steamer from Mud Harbor reached the city, and the sun was sinking behind low, gray clouds. Maggie Fishbone was dizzy and seasick and so nervous, she felt like she had swallowed an eel. She gripped her suitcase, stumbled off the gangplank, and followed Sister Immaculata through the docks and out into the street.

The noise was deafening. Motorcars and trucks trundled past and trains clanked on iron bridges overhead. Clouds of steam hissed from gratings in the sidewalk. The air smelled of smoke, garbage, and a bunch of other things Maggie did not recognize. And there were people everywhere. A group of young men staggered by; one was playing a bugle and the others were singing in a foreign language. A woman bustled past with a huge purple cabbage in a basket. A man stood beside a baker’s cart, yelling about hot pies and pretzels.

Back in the orphanage in Mud Harbor, Maggie had heard stories about the city. The fish heads for the orphans’ supper came wrapped in newspapers, and the orphans read the newspapers and whispered about them at night in the dormitory. The city was stuffed full of wickedness, everyone knew that. Huge alligators lived in the sewers. Shadowy, hulking monsters lurched through the streets at night. Bakers stole children, chopped them up, and made them into pies.

Maggie didn’t believe the stories. Not really. But all the same, she frowned suspiciously at the pies on the baker’s cart.

Sister Immaculata’s black habit fluttered and her mouth was set in a determined line as she strode through the crowd. She checked the time and asked for directions, then they boarded a streetcar and found a seat. Maggie was uncomfortably squashed between the window and Sister Immaculata (who felt lumpy and bony, as if she were made out of potatoes and cutlery), and had to crane her neck to peer out as they rattled through the streets. They passed statues and steeples and buildings that reached so high into the sky that Maggie felt like they were traveling along the floor of a deep canyon. Advertising signs flashed and sparkled. Far above, she glimpsed an airship—a shadow against the clouds, as big as a whale. She caught her breath as it glided overhead.

Sister Immaculata cleared her throat and said, “Well, Magdalena. You’ve got a devil of a temper, and you acted like a hooligan, time and again. Even as a baby you had a shriek like a banshee . . .”

Maggie scowled out the window and tried not to listen. She had heard the story a hundred times. How she’d been left on the doorstep of the orphanage, wrapped in a scrap of sailcloth and tucked into a mackerel box. How the nuns had chosen the names Magdalena (after the saint, of course; the nuns were very keen on saints) and Fishbone, because her angry screams had sounded exactly like the seagulls in a gutter nearby, fighting over a herring bone.

She sighed crossly.

Sister Immaculata was still talking. “… And now look where it’s landed you. You’ve only got yourself to blame. You’ll be tamed now, that’s certain. Tamed good and proper.”

Maggie shrugged, still scowling. There was nothing to say about that. Sister Immaculata had been saying similar, discouraging things all day, and Maggie was feeling sick with dread.

They clambered off the streetcar on a busy street lined with storefronts and apartment buildings. It had started to rain, and people were hurrying along, heads bent.

Sister Immaculata unfolded a letter and studied it in the light of a streetlight. She frowned. “This way,” she said. “Hurry up, or we’ll be late.”

They followed the street for a few blocks, turned a corner, and came to a high, dark building; a looming, spiky shape of gables and chimneys. Set in the wall was an archway, with words carved into the stone.

THE MIDWATCH INSTITUTE

for Orphans, Runaways, and

WAYWARD GIRLS

Maggie felt her heart lurch. She took a breath and gripped her suitcase tightly. This was her last chance to escape. But before she could take a step, Sister Immaculata grabbed her by the wrist and snapped, “Oh no you don’t.” And she dragged Maggie up the stairs to the door and rang the bell.

They waited. Traffic rumbled past. A cat darted across the narrow street and disappeared behind a row of garbage cans. Two women walked by. As they passed, one of them said, “Another poor kid. They go in, but you never see them come out again, do you?”

Maggie swallowed and tried to stop herself from shaking.

At last, the door was opened by an enormous woman wearing an apron. She was around the same size and shape as the door, and she had a forbidding expression.

Maggie took a step backward.

Sister Immaculata’s fingers tightened on her wrist. “I’ve brought a wayward girl,” she said.

The woman frowned, let them in, then closed the door behind them with a heavy thud. Somewhere deeper in the building, an organ was playing a slow, melancholy tune. As the woman led them along a short passage and into a hallway, a line of girls appeared. They were wearing long, gray, hooded cloaks, and they walked silently past with their eyes down. Sister Immaculata watched them until they disappeared around a corner, and she gave a satisfied little nod.

On a bench in the hallway, two dejected-looking girls of about Maggie’s age sat waiting, each with a shabby suitcase.

The large woman pointed to an office window. Above the window Maggie read:

INSTITUTE OFFICE

Miss Fortnightly

Secretary

Admissions on the last day of the month.

By Arrangement.

Strictly 5pm–6pm only.

Sister Immaculata tapped on the window. A thin, gray-haired woman slid it open and peered out, frowning over her spectacles. She said, “Admissions?” and didn’t wait for a reply. “Name?”

“Magdalena Fishbone,” said Sister Immaculata.

“Fishbone?” The secretary ran her finger down a column in a ledger, nodded, and said, “Yes. You brought the letter?”

Sister Immaculata passed it over. The secretary read it carefully, then pointed at the ledger. “Sign here.”

As Sister Immaculata signed her name, the line of silent girls filed back in the other direction. Maggie shivered. They definitely looked tamed. Tamed and miserable.

Sister Immaculata gave Maggie an awkward pat. She said, “Well. That’s done. I’ll be off or I’ll miss the steamer.”

Maggie frowned at the floor. If she tried to say anything, she knew she would cry.

Sister Immaculata patted her again. “Goodbye, Magdalena,” she said, not unkindly. She hesitated, as if she was going to say something more, then turned and followed the large woman away. After a few moments, Maggie heard the front door close behind her.

The secretary frowned at her impatiently. “Sit.” She pointed.

Maggie went over and sat on the bench between the other two girls. One was pale and thin, and a bit taller than Maggie. Her mousy hair was in a long, straggly braid, tied off with a piece of string. Maggie tried to catch her eye, but she was gazing miserably at her own boots and did not look up. The other girl was shorter and stocky, with cropped, spiky dark hair. One of her hands was bandaged and in a sling. She was scowling at something in the distance, her eyebrows an angry black line.

The gloomy organ music echoed around the hallway. Maggie could feel the sadness seeping into her like a trickle of cold water. This was straight-up horrible. She should have run away when she had the chance.

No girl from Mud Harbor Orphanage had ever been sent away to the city before. At the orphanage, good girls got jobs as housemaids, not-so-good girls became kitchen maids, and leftover girls went to work at the fish cannery.

Maggie had always known she would end up in the cannery. She knew it, and everyone else in the orphanage knew it too. Good girls were quiet and obedient and sewed like angels. Good girls were like Veronica Floodtide, who had made a set of cushion covers in impeccable cross-stitch, or Agatha Cormorant, who had gotten a position as a housemaid in one of the big houses on the hill behind the town. All the nuns said Maggie was too impatient and too bad-tempered. She was not much good at anything, and her sewing was appalling. The shirt she was supposed to be hemming was so crumpled and grimy and damp that Sister Penitencia said it looked like it had been torn off a drowning man.

She was going to be a fish-gutter at the cannery.

Which was certain to be dreadful.

But then she had pushed Ned McCoy into the harbor, and that changed everything.

Ned McCoy had been swaggering around the cannery wharf, tormenting a bunch of little kids—flicking stones at them and making them cry. Maggie had been passing by on an errand for Sister Assumpta, and, without thinking, she had flung herself at him. She was half his size, but her attack had been so unexpected she had knocked him off balance; he had skidded on seaweed, arms flailing, then toppled into the harbor with a mighty splash.

When he surfaced from the green, murky water, wet and slimy and spluttering for air, all the little kids were cheering, and the watching longshoremen and fishermen were laughing. It had been Maggie’s proudest moment. Despite everything that had happened since, she couldn’t help smiling at the memory.

But of course, Ned McCoy was the cannery manager’s son. Which was straight-up unfortunate. Because now even the cannery didn’t want her.

She was no good at anything, and no use to anybody.

Which is how she had washed up here, at The Midwatch Institute for Wayward Girls.

It was all very discouraging.

The clock chimed, and the secretary counted the three girls, ruled a line underneath their names, and closed the ledger. She rang a bell and the large woman returned. The secretary said, “That’s all of them, then. Take them through, if you please, Mrs. Carnaby.”

The girls picked up their suitcases and followed the large woman along a narrow passage, around a corner, and up a short flight of stairs. The organ music was louder here. Maggie could feel the deep, sad notes rumbling through the floor.

The woman opened a door into a large, shadowy room full of tables and chairs. High up on the walls were polished wooden boards with lists of names in gold letters, but it was too dark to read them, or why they had been recorded.

At the far end of the room was a platform, where an extremely tall lady, as upright as a ruler, was playing the organ. She had a grim expression and a black eye patch, and she wore an old-fashioned black gown that reached to the ground. Her dark hair had silvery streaks in it, and it was coiled on top of her head, making her look even taller.

She turned her head as they came in. “They have departed? Excellent. Thank you, Mrs. Carnaby. That went rather well, I think.” With her long fingers, she pulled out a couple of knobs on the organ, flicked a row of switches, and struck a chord.

There was a hiss, a spark, and a loud crack that made them jump.

Suddenly, a firework shot out of one of the organ pipes and exploded above their heads with a brilliant red flash and a shattering bang.

Chapter Two

The tall lady played several more chords, and more fireworks shot out of the organ pipes, bursting overhead and scorching the ceiling.

They all gasped.

“Holy mackerel!” said Maggie.

The lady stood up and came toward them, leaning on a cane. “Welcome,” she said, smiling. Behind her, the organ wheezed and sparked. “An explosion calliope,” she said. “A marvelously expressive instrument, don’t you agree? It does create a formidable atmosphere, which is rather useful on occasions such as this. I am Miss Mandelay, the Midwatch Institute director. This is Mrs. Carnaby, our cook. Thank you for your help, Mrs. Carnaby.”

The large woman’s eyes were twinkling. Suddenly, she seemed friendly. She said, “Welcome, girls. Well, I’m off. I’ve got a stew on.” She pulled a ladle out of her apron pocket, waved it cheerfully at them, and strolled away.

Miss Mandelay strode over to the door and opened a panel beside it, revealing a row of electrical switches. She pressed several of them and the lamps overhead lit up, humming and flickering.

Maggie gazed around, bewildered and blinking in the sudden brightness. Despite the smoke from the fireworks, and the many scorch marks, the wooden boards on the walls gleamed. One read,

For Quick Thinking in a Tricky Situation. Another,

For Remarkable Determination. And another,

For Making the Best of a Horrible Catastrophe.

“Welcome,” said Miss Mandelay again. “Your names, please.”

The girls glanced at one another. Maggie swallowed nervously and said, “I’m Maggie—Magdalena—Fishbone.”

The pale girl murmured, almost too quietly to hear, “Nell Wozniak.”

The girl with her arm in a sling was still frowning. She did not speak for a moment, then she muttered, under her breath, “Sofie Zarescu.”

“Welcome, all three of you,” said Miss Mandelay. “Now, no doubt you are feeling tired and hungry. There will be supper shortly, but we will have cake now. Follow me.” She headed toward a door on the far side of the room. Despite limping and leaning on her cane, she walked quickly, with long, loping strides, and they had to hurry to keep up.

Noises were starting up in all directions. Maggie heard running footsteps, then a door banged. Someone laughed, and a phonograph began playing dance music.

They passed a classroom. Inside, two girls wearing goggles were watching a tiny model of an airship fly in a sputtering circle in the air above their heads.

“Good evening, Kate. Good evening, Anna,” said Miss Mandelay as she strode past.

“Good evening, Miss Mandelay,” said the girls—without taking their eyes from the airship, which was emitting sparks and little puffs of steam.

Miss Mandelay led them outside, across a courtyard. It contained a large tree, a rusty basketball hoop on one wall, and a battered motorcar that looked like it was made out of several different vehicles bolted together. It had red fenders and green doors, and the name

Camille was painted on the side in slightly wonky letters. Several girls were clustered around, and one was peering underneath with a lantern. She said, “Okay,” tightened something with a wrench, and scrambled to her feet. The girl in the driver’s seat fiddled with some levers, and one of the others yanked the starter handle around. The motorcar coughed, lurched forward a few inches, made a bang like a gunshot, and stopped with a jerk.

“Too much spark, I believe, girls,” said Miss Mandelay. She opened a door and Maggie, Nell, and Sofie followed her back inside and up some stairs. A group of girls appeared, carrying a long, coiled-up rope ladder between them, and began to climb a staircase. “Do take care on the roof,” Miss Mandelay said. “The rain will make the tiles slippery. Check your knots.”

“Yes, Miss Mandelay,” they replied.

She strode on, around a corner and along another passageway. “Here we are,” she said, and she opened a door into a cozy sitting room. It was full of comfortable-looking couches and little tables and rugs. The walls were crowded with books and pictures and ornaments.

“Take off your coats and sit down,” Miss Mandelay said. “The bathroom is through there”—she pointed—“if you require it.”

They hung their coats on a hat rack, used the bathroom, then sat in a nervous row on a couch. Nearby was a tea trolley with a steaming brass urn, cups and plates, and a cake stand piled with beautiful little cakes.

Miss Mandelay sat down and said, “Will you have hot chocolate?”

Maggie nodded. Nell whispered something too quietly to hear. Sofie frowned and didn’t answer.

Miss Mandelay filled the cups from the urn. Maggie took a sip. The hot chocolate was rich and delicious, quite different from the watery cocoa they sometimes had at the orphanage. She drank some more and put the cup and saucer down on a nearby table.

Miss Mandelay moved the cake stand closer and passed them each a plate and a cake fork. Then she leaned back, resting one foot on a stool. “Aluminum,” she said unexpectedly, rapping her leg with her knuckles. It made a hollow clang. “A misadventure, some years ago. This one is better than new, the doctor says, but still somewhat inconvenient, on occasion. These little cakes are very good. Mrs. Carnaby made them especially for your arrival. Do help yourselves. Take two or three to start with.”

Maggie hesitated, then took the closest cake, which was shaped like a frog. It was sweet and crumbly and filled with strawberry cream. She finished it in three slightly messy bites.

“Little cakes like this are called

petits fours in French,” said Miss Mandelay, taking an owl-shaped cake and eating it quickly and neatly. “It’s good to know how to say at least a few things in French. Apart from anything else, it tends to impress people.”

Maggie couldn’t think of anything to say about that. She took another cake, a toadstool. It had bits of crunchy toffee inside. Nell nibbled a rabbit. Sofie ignored the cakes and frowned at the fireplace.

“Naturally, you should learn any language you can,” Miss Mandelay went on. “There is nothing more useful. All our girls study at least one foreign language. You never know when you will need it. I once managed to escape from a rather perilous situation in a nightclub in Casablanca using only a few carefully chosen words of Swahili.” She took another cake. “I am a great believer in learning as many useful things as possible. You see, when I was a young girl at boarding school, the lessons we were taught were useless. Utterly useless. So a friend and I formed a secret club and dedicated ourselves to learning as many useful things as we could. We taught ourselves how to use secret codes and signals, and we crept out of the school at night to practice tracking in the woods. We trained small animals to send messages between us, and we learned to swim and climb trees. It was tremendous fun.”

She pointed at a framed photograph that hung on the wall. It showed two girls wearing old-fashioned frilly white dresses. The younger Miss Mandelay was perfectly recognizable, even without her eye patch; a tall girl with a determined expression.

Adelia was written underneath her picture in an elegant script.

Miss Mandelay smiled at the photograph reminiscently. “Of course, in the end, we were both expelled. But that is by the by. Now.” She leaned forward and looked intently at them. “Please tell me about yourselves. And perhaps you have some questions for me.”

Maggie had so many questions, she didn’t know where to start. She said, indistinctly, “What exactly—what is—?” She swallowed her mouthful and said, a bit too loudly, “Good gravy. What is actually going on here?”

Miss Mandelay laughed. “It’s true, things here are not exactly as they first appear. I must apologize for the deception you experienced when you arrived, but it was quite necessary. Reputation is so important, don’t you agree? The Midwatch’s reputation is extremely grim, and I expect all our girls to work hard to uphold it. It is so very useful to us in the work we do. Because—”

She was interrupted by a jangling bell. She picked up her cane, strode to a telephone on the wall, held the handset to her ear, and said, “Hello? Miss Fortnightly? Yes?”

There was a crackling sound. Miss Mandelay said calmly, “I see. A message from the commissioner. Another sighting? Where, exactly?” More crackles, then she said, “Yes. I will set out immediately.”

Frowning, she placed the handset back on its rest. “I must go, girls. Please wait here, and I will send someone to look after you.” She took her hat and coat from the hat rack, then turned back and said, “I’m sure you are feeling strange right now, but have no doubt about this, you are all very welcome. This is your home now, and I do hope you will be happy here. Happy and useful.” She smiled. “And be sure to finish those cakes.” And with that, she strode quickly away, closing the door behind her.

Copyright © 2025 by Judith Rossell. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.