THE WHOLE MESS STARTED WHEN Owen was fired at the end of summer term. Estie had been right at thirty-six weeks and two days when he came home and announced that his position as an English professor at Norton College had been terminated. “Financial exigency,” he said, his eyes puffy. It was a good hour- and-fifteen-minute drive from Norton to Briarwood, where he and Estie lived, and Estie guessed he’d cried all the way home.

He spent the next thirty minutes hauling in boxes of books from his car and stacking them neatly in the closet of what was going to be the baby’s room, and the ten minutes after that cleaning up cat vomit. The cat, Herbert, disapproved of strong emotions.

“So what happens now?” Estie asked. “Do you look for another position?”

“I don’t know,” Owen said. “No. Not yet. They don’t post English jobs until October.”

Estie felt her stomach clench, or maybe that was just Braxton Hicks. It was the end of July, and the baby was due in late August.

“What are we going to do?”

“I don’t know,” Owen said again. “It just happened. I need time to think.”

Estie nodded, ignoring the baby’s kicks of protest against her ribs. The truth was, she’d been waiting for something like this to happen ever since she’d gotten pregnant, possibly even before. Estie knew she’d been lucky so far: the major disasters of her life up to this point—her parents’ divorce, the not-quite-breakup with her college boyfriend, Dan—had been relatively minor. But if reports of tornadoes and school shootings had taught her anything, it was that luck was fleeting and complacency dangerous: the other shoe was out there, dangling, ready to drop, and it was important not to be caught off guard. Except that Estie had been caught off guard. Owen losing his job felt like a failure of imagination on her part: it had never occurred to her that a tenured professor could be laid off. How had she not considered this possibility? Why had she not made any backup plans?

Then again, it wasn’t as if much had been going according to plan lately. Take, for instance, the pregnancy itself. Yes, Estie was glad she was pregnant—she was; she was really—but she’d always imagined that she would be the one setting the schedule, the one who would some day find herself weeping in the diaper aisle at Target, triggered by a passing stroller or the photo of some celebrity’s sleeping baby, and then rush home and declare it was time. Instead, it was Owen who had made the decision back in January, after they’d gone to one of Estie’s coworkers’ baby shower. The coworker, Jillian, was the receptionist at Big Earth, the artisan tile factory where Estie worked as a glazer, and she was the kind of person who emailed everyone photos of her positive pregnancy test, then separately cornered each of her coworkers and forced them to place a hand on her small mound of belly while, flushed with pride, she asked, “Can you feel the peanut kick? Now? And now?” When it had been Estie’s turn to feel the baby move, Jillian had guided her hand so far down along her abdomen that Estie’s fingers had brushed against the waistband of Jillian’s underwear. “Okay, I feel it, I feel it,” she’d said, even though the only thing she’d felt was Jillian’s hot skin.

“She could’ve at least bought me dinner first,” Estie complained to her best friend, Alice, and Alice, who worked at a start-up in Chicago that was developing a tartar-detecting smart toothbrush, had laughed: “At least there’s only one of her,” she’d said. There were four pregnant women in Alice’s unit alone.

Jillian’s shower had been held at Precious Insights, a converted movie theater that specialized in big-screen 4D gender-determination ultrasounds that you watched from “luxurious stadium seating” while sipping mocktails from a sippy cup.

According to Jillian, vanity ultrasounds were all the rage and women-only baby showers were passé, but then again, Jillian also liked wearing maternity tees that said things like “Don’t eat watermelon seeds” and “You’re kicking me, smalls.” Still, there were going to be cupcakes, so Estie had figured that she and Owen would spend a pleasant afternoon rolling their eyes at each other and feeling superior. And the afternoon had certainly started out that way, with Owen grimacing at the Precious Insights slogan, which was painted on the wall in a precious, impossible-to-miss script: “The Largest of Blessing’s Are Those That Are Small.” Nothing set Owen off like apostrophe errors in corporate logos.

“See,” he said, pointing to the same error in the program the hostess handed them. “If you’re not careful, these mistakes just perpetuate themselves.”

They’d found seats in the right corner of the theater, near the emergency exit because you never knew, and looked on as Jillian hoisted herself up on the cot in the center of the room and hitched up her maternity blouse without hesitation. The ultra- sound tech, a woman in blue scrubs and lots of blue eye shadow, smeared jelly on Jillian’s abdomen, which, unsheathed, looked plastic and fake, crisscrossed by pale stretch marks and so taut with baby that her belly button appeared to be turned inside out, like one of those pop-up timers people used to cook turkeys. Then the lights dimmed, Jillian and her husband clasped hands, and the Dolby Surround Sound speakers began blasting the whooshing of the baby’s heart into the observation area. A few seconds later, the large screen behind Jillian flickered to life and there was the baby in all its yellow three-dimensional glory. Next to Estie, Owen exhaled loudly, as if he were the one who was nervous.

“Here is Baby’s foot,” the ultrasound tech said, pointing. “Here are Baby’s little toes.” She moved the wand a little, then announced, voice bursting with pride, “And here’s Baby’s little boy part,” as if she’d just attached the penis to the baby herself. Estie had expected Owen to make some sort of crack about the solemnity of it all, but all he did was lean closer and squeeze her knee. The tech slid the wand over a little more, and on the monitor, the baby’s blurry yellow face filled the screen, shifting in and out of focus as if he were pressing himself against a fleshy yellow wall, a tiny Han Solo trapped in carbonite. You’d make out the orbs of his eyes and his flat little baby nose, and then they would recede and melt into the background, or worse, transform into dark hollows as if the baby were all skull, as if he’d forgotten to grow muscle and skin. “It looks like an alien,” Estie started to say, but just then the baby yawned and rubbed his eyes with a small fist, looking as aggrieved as any human interrupted in the middle of a deep sleep.

“Wow,” Owen had whispered, his voice reverent. “I mean, wow.” And just like that, getting pregnant became yet another milestone in a long list of milestones that refused to unfold as seen on TV—a first kiss full of spit and onion rings, a first high school party without beer or weed, first-time sex without soft lighting or simultaneous orgasms. Instead of swelling violin music and a gentle baby wakeup call, what Estie had gotten was Owen shuffling her off to the bedroom the moment they got home, then undressing her from top to bottom, all business, no kissing. “Sheesh,” Estie had said, “what’s your hurry?” Her fingers were still sticky from the cupcakes, and there was a smudge of blue frosting at one corner of Owen’s mouth, but his urgency had made her feel irresistible—he was usually so calm, so measured in everything he did—and so she’d helped him with the clasp of her bra, with her zipper, with her socks, with his, and tried not to feel self-conscious and fat when he lifted her onto the bed and climbed on top of her.

“Feel my heart,” Owen had said once he was inside her, and Estie could feel it, beating rapidly against her own chest. She waited for Owen to pull out and put on a condom, and when he didn’t, she’d said, “Wait.” Owen paused, resting his full weight against her so that she was pinned. “I really really love you,” he told her. “We’re adults. It’s time.”

“Be serious,” Estie said, squirming.

“Come on,” Owen whispered, still on top of her, his lips against her ear. “I want you. I want you and me and a baby of our own.”

Estie swallowed hard, suddenly aware of Owen’s bony ribs against her chest, his jutting hips against her inner thighs. She could have told him to stop, but doing so felt pointless—she didn’t know what she wanted, just what she ought to want. She was thirty-two. She was married and gainfully employed. She’d always figured she’d have a baby someday. She closed her eyes and tried to relax. Of course she wanted a baby. Of course she did.

“Okay,” she told Owen. “Okay. Let’s do it.”

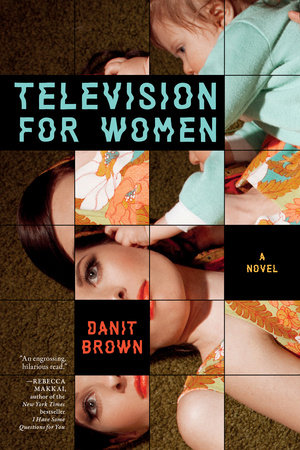

Copyright © 2025 by Danit Brown. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.