BRING ON THE DANCING HORSES When I call my parents, my mom tells me my dad is busy teaching a class on the internet. That is, the class is in a classroom but the topic is the internet. More specifically, he’s teaching seniors—that is, old people—how to blog, write anonymous comments on news articles without panicking, poke their children on Facebook, and get away with not writing h, t, t, p, colon, forward slash, forward slash, w, w, w, dot before every web address.

I had no idea my dad liked the internet so much. “Who said anything about like?” my mom says. I can hear her clicking away at her keyboard in the background.

My dad is retired—or was. Is it that they need the money? I fantasize about a heretofore unknown gambling problem, hush funds, love children. My mom sells my old comic books and De La Soul cassingles on eBay. She doesn’t know I know. Every so often I’ll think about stuff I loved in my youth, and a search inevitably brings up her dealer name.

I amp the bidding when it seems safe. You could say I’m looking out for her. But how is it that her four grown kids have neglected their parents’ financial needs?

I go to bed with a nagging sense of guilt, though this is how I usually go to bed.

≈

My girlfriend, Tabby, reviews science fiction for a living, which just goes to show you that America is still the greatest, most useless country in the world.

She went to Penumbra College in Vermont and is ABD in comparative literature at Rue University. She’s been ABD ever since we met, back when I didn’t know what it stood for. Her dissertation is about one or possibly all of these things: manservant literature, robot literature, and the literature of deception.

Tabby is considerably older than me, and by considerably I mean over ten years. I told my parents five, but I don’t think they believed me. Tabitha Grammaticus remembers not only life before the internet, but life before the affordable and relatively silent electric typewriter.

She reads fast, writes faster. She does monthly columns for the

California Science Fiction Review,

Exoplanets magazine, and the website for the Northwest Airlines’ Frequent Flier Book Club, which is getting a soft launch.

≈

I didn’t think it was possible for someone to read as fast as Tabby does, and for a long time I assumed she was a skimmer. But whenever I’d quiz her on a novel that we’d both read, she knew every detail. I’d sit there with the book open and ask things like: “Who answers the door in the middle of chapter 7?”

I tried to keep up with Tabby’s reviewing, but it’s hard when someone’s so prolific. I am not friends with many writers, mostly because that means having to read all their articles, stories, essays, books, and even poetry. They expect you to have read it all. With Tabby, I tried. I really did.

But she’s what she calls a stylist. I gave up on her Exoplanets column after the third one. I got stuck on the opening line: “All time travel is essentially Oedipal.”

Tabby is a brilliant genius in her own way, but sometimes I worry that she is turning into an alien. Lately we don’t go out much, and she has taken to wearing what she calls a housecoat about the house. Whenever I’d come across the word “housecoat” in a brittle British novel of misaddressed correspondence and quiet adultery, I would try to picture what was meant. I was never sure, but surely it isn’t this thing that Tabby more or less lives in, a sort of down-filled poncho with stirrups.

≈

At the same time I’m attracted to this girl at work. I don’t even want to know how old she is. My guess is that she’s younger than me by a margin nearly as great as that separating me from Tabby. But what do I know about age? I thought Tabby was my age when I met her. I’m not a good judge of these things, possibly of anything.

The girl at work. I think English is her second language or possibly her third. She has a lisp and does crazy things with her hair. Her name is Deletia. I think it’s the most beautiful name in the world.

Here’s a secret. I wrote that down on a Post-it once—You have the most beautiful name in the world—and carried it stuck to the inside of a folder. All day I was hideously excited as I sat at my desk, roamed the corridors. Then I forgot about the note for a week. When I saw it again the words looked strange, like someone else had written them. Before throwing it away, I used the sticky edge to clean out the crevices of my keyboard.

≈

I have two older brothers, whom I despise, and a younger sister, whom I adore. My brothers have always been exceedingly nice to me, including me in all manner of conversation and sport, yet I can’t stand the sight of them. At least individually. When the three of us sons are together, my ill will dissipates somewhat, into a tan-colored mist of indifference. My sister, Grace, on the other hand, speaks sharply to me and expects me to do things like pick up her dry cleaning and find her cheap tickets to Cancún on the internet. I mean the real Cancún, not some virtual

playa. But she’s the baby of the family and I’m happy to oblige.

We children all live in the city, and gatherings are complicated for me. If it’s me, my eldest brother, Dan, and my sister, I get argumentative the second I walk in, under the impression that he is picking on her, being the bully that he undoubtedly is. If it’s me, my other brother, and my sister, I’ll tell jokes nonstop, poorly thought-out jokes that hinge on antiquated wordplay. I’m trying to defuse the tension caused by the fact that this brother is a withholding control freak.

In fact, my brothers are exceedingly nice to my sister as well, and she does not speak sharply to them or expect them to run her errands. Sometimes I think she respects them because they make money and I don’t, really. Or because their wives are elegant, capable women, and Tabby is something of an eccentric and a bit of a slob.

Once I was on a bus going crosstown and saw Grace and my brothers walking out of a restaurant, laughing. They looked gloriously happy. Dan posted a picture of their lunch on Facebook. I don’t know what he was thinking.

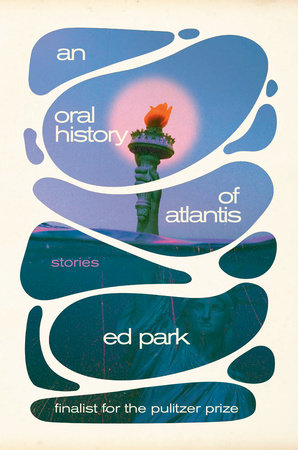

Copyright © 2025 by Ed Park. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.