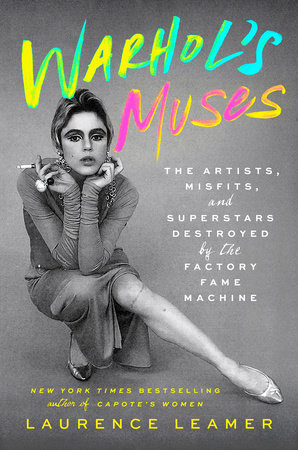

1.

Riding the Whirlwind

In 2022, nearly four decades after his death, Andy Warhol's silk-screen portrait of Marilyn Monroe sold for $195 million, a record amount for an American painting. Warhol's iconic look (a silvery wig with pasty features and a slim, black-clothed silhouette) are instantly recognizable-almost a "personal brand" before such a concept even existed. He is the most famous and successful twentieth-century American artist.

Warhol is the defining figure of pop art, an artistic movement that burst forth in the early sixties, taking fine art on a wild roller-coaster ride. In the same way that jazz is the first uniquely American music, so pop art is profoundly American, a pure product of mid-twentieth-century American culture. Pop art took the common artifacts of life-including cartoons, movie star shots, and advertisements-and blew them up into stunning images. Warhol and his fellow artists democratized art, taking it out of the sedate salons and into a garish new world.

But Warhol impacted American culture and life far beyond his art. Although he lived within a narrow world, he understood what was happening in society far better than the cultural and political radicals of the sixties, with their glorious visions of the future. He pierced America's facile optimism and saw a society riven with alienation. By his own making, Warhol became something of a cartoon figure, yet he was a messenger carrying a dark message.

As an emerging pop artist, Warhol sought a way to enter the world of the rich and famous and, once there, to make his artwork an integral, must-have feature of grand homes from Manhattan to Bel Air to Palm Beach. In early 1960s America, most artists had little interest in such self-promotion. Since only a niche audience for contemporary art existed, they saw little reason to reach out beyond their world. Warhol looked beyond the previously defined role of "artist" in society. He did not want to be sequestered in his garret studio, cut off from the world.

Warhol sought to be famous beyond measure. That was his great challenge: not the art he quickly assembled in the Factory, but making himself such an iconic figure that art connoisseurs could not live without a Warhol on their walls.

Warhol was not a naturally gregarious social creature. Nonetheless, to further his career and his ambition, he went out almost every evening, soaking up both the high-society world he wished he'd been born into and the low-life world that fascinated and repelled him. He knew that cultivating a unique image was the best advertisement for himself and his art.

Warhol also knew he could not get where he wanted to go by himself. He was, by his own admission, a weird-looking gay man in a world and an era that wasn't hospitable to such as him. "I really look awful, and I never bother to primp up or try to be appealing because I just don't want anyone to be involved with me," he said.

Alone, Warhol could only travel so far in society's rarefied circles. He realized he needed to be around stunning women. They would raise his social cachet dramatically and bring him the publicity and public adulation he so desired.

With a beautiful woman on his arm, a man-even a quiet, awkward man (as Warhol understood himself to be)-could go almost anywhere. So, Warhol started to collect these women, like trophies or playthings. He called them his Superstars, gave several of them new names, featured them in his underground films, and accompanied them to places he could not have gained admittance to alone.

By the time Warhol met most of these women, he had completed much of his so-called "major" art, but his Superstars helped to raise his profile and his work into the stratosphere. While the Warhol Superstars did not necessarily influence the making of his work, they played seminal roles in its wide acceptance-and they were integral to what is possibly Warhol's greatest and most enduring creation: himself.

These women were not just his Superstars, they were his artistic muses who helped turn the Pittsburgh-born son of Eastern European immigrants into international artist Andy Warhol. They talked to him every day and were key to his emotional life. And while many of them have received attention, their contributions to the artistic world they helped to define-and their own artistic ambitions, personal struggles, and occasional triumphs-have been largely overlooked. Just like muses have been across time.

These women were intriguing and complex. They lived dramatic, often troubled lives. While the allure of Warhol's downtown bohemian New York was its unconventional, carefree, and often dark atmosphere, most of these women came from upper-class families whose members rarely traveled to such a downscale world. Their presence was its own form of rebellion from society's norms. Warhol often christened them into their new lives by bestowing upon them new names that reflected not who they'd been, but who they wanted to be. Or at least, who he wanted them to be.

The first Superstar was Jane Holzer (Baby Jane), whose father had extensive real estate holdings in Palm Beach. Holzer had an incredible mane of blond hair that set her apart from her contemporaries.

But Holzer had nothing like the lineage of her successor, Edie Sedgwick, whose ancestor landed in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the seventeenth century. Sedgwick was a petite beauty whose features the cameras loved.

Brigid Berlin's father was the chairman of the Hearst Corporation, giving his daughter keys to New York's elite world. Often rotund and always foulmouthed, Berlin lived to offend her mother.

Mary Woronov's life changed when her mother married a prominent Brooklyn surgeon. Tall as a Viking princess and unwilling to let Warhol change her name, Woronov took great pride in exuding a fierce, almost masculine aura.

Susan Bottomly's (International Velvet) mother was a Boston Brahmin. Although she was only seventeen when she first met Warhol, Bottomly was sophisticated beyond her years.

Susan Mary Hoffmann's (Viva) father was a highly successful lawyer in Syracuse, New York. With a wicked wit and savage intelligence, Hoffmann was game for almost anything.

Isabelle Collin Dufresne (Ultra Violet) had an upper-class European background. Salvador Dalí's former lover had an erudition unique among Warhol's muses.

Not all the Superstars were from privileged homes. Christa Päffgen (Nico) was brought up in decidedly humble circumstances in Germany during World War II.

Ingrid von Scheven (Ingrid Superstar) came from a modest New Jersey background.

James Slattery (Candy Darling) hailed from a lower-middle-class home on Long Island.

"The superstar was a kind of early form of women's liberation," argued Danny Fields, a music manager close to Warhol. "They were so smart, beautiful, aristocratic, and independent. . . . Everybody fell in love with them. . . . They're the women we all want to worship. . . . At the same time, they were very destructive people-self-destructive and other-people destructive. They were riding the whirlwind."

In a society that still widely disregarded and disrespected homosexuality, Warhol's Superstars softened his queerness for public consumption and brought him a dose of added glamour, even respectability. Those women from largely upper-class families took Warhol into a social world he could not have otherwise moved through. Unable to unlock those doors, he would have had difficulty developing the contacts and publicity crucial to his rise. Without his Superstars, Warhol might never have become a world-celebrated artist.

From Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe to Elizabeth Taylor and Judy Garland, many of Warhol's most memorable portraits are of iconic women of the age. This peculiar little man created images of strong, beautiful women as immortal as the subjects themselves. His ever-changing array of Superstars were, for the most part, not the subjects of his art, but they played indispensable roles in elevating him into the world-renowned artist we know today.

Warhol's Muses is the story of these women and what happened to them when they entered Warhol's world.

2.

Party of the Decade

April 1964

Warhol's show at Manhattan's Stable Gallery in April 1964 was the most important event so far in his professional life, and he had prepared for the opening with meticulous concern.

The artist began by creating four hundred faux boxes of Brillo pads, Heinz ketchup, Kellogg's Corn Flakes, and Mott's apple juice. A child of his discontented time, Warhol wanted to stick it to the establishment and the mandarins of high art who controlled the content of the museums. And what better way to do that than to create an anti-high art, turning images of grocery store products into art?

But how to display it? This was industrial art. It would not do to set the plywood boxes off by soft lighting like the Mona Lisa at the Louvre. He had the wooden boxes stacked up one on top of another, as if in a warehouse waiting to be hoisted onto a truck for delivery to supermarkets.

To most viewers in 1964, such a tableau would not be recognizable as "art" at all. Art was an oil painting in a frame. A bronze sculpture in a park. Maybe a perfectly composed photograph. Not a bunch of empty boxes piled on a gallery floor.

Warhol was an impresario as much as an artist. He had realized early on that anything could be art-much like the Dadaist Duchamp (and his infamous urinal) had done half a century before. And now, thanks to his witty ideas and a canny knack for self-promotion, Warhol was emerging as a key figure in a burgeoning pop art movement that turned artifacts of mass culture into art. He did not run from controversy. He knew that some considered his work-the whole pop art movement-to be little more than an embarrassing joke. Warhol embraced the controversy.

Warhol knew this show would get attention, but he did not necessarily think the pieces would sell out. Maybe a few items would go for the modest $200 to $400 asking price. After all, the publicity generated was already noteworthy, and the line to get into the gallery that night stretched down the block on East 74th Street. But as the evening wore on and nothing sold, Warhol had reason to be discouraged.

At least Warhol had Robert and Ethel Scull. The couple had promised to buy twenty Brillo boxes, paying $300 a piece or a neat $6,000. The Sculls owned a fleet of taxis called "Scull's Angels," hardly a business that brought them much social contact with the upscale residents of Manhattan. But over the last few years, the couple had slowly insinuated themselves into the art world, cannily selecting artists they admired and slowly acquiring a few pieces from them, then more. By now, they were well on their way to being leading pop and minimalist art collectors. This taste and artistic glamour-not their money-was the key that opened previously locked social circles to the couple. It was a lesson Warhol observed closely.

After the opening, the Sculls agreed to cohost a party for Warhol with the socialite Marguerite Littman. The affair would be held at Warhol's scruffy studio at East 47th Street between Second and Third Avenues. It was ample space for a big party, almost eighty feet long and half as wide, with two filthy bathroom stalls.

When Warhol had moved in at the beginning of the year, the walls had been grimy and crumbling. His assistant, Billy Linich (later called Billy Name), silvered the walls, applying aluminum foil to everything, until the space looked like a poor man's spaceship. In the middle of the room sat a red sofa that had been picked up off the street. It was so soiled that it probably should have been cordoned off, or better yet heaved into a dumpster downstairs. Instead, it was the focal point of the room. Name and his friends called the studio the Factory. The name stuck.

A few years earlier, almost no one of consequence would have taken a freight elevator up to the fifth-floor quarters to celebrate an artist obscure to nearly everyone beyond avant-garde circles. But by the mid-1960s, even more socially conservative New Yorkers were going places they once would have disdained. They were looking for good times in new places and, in doing so, unknowingly challenging the ways and rules of traditional society.

Social customs among the upper class in Manhattan had been clearly defined for most of the twentieth century. People of consequence lived on the Upper East Side. They saw their friends in privileged places: the Metropolitan Club, the Yale Club, and the Union Club. They went nightclubbing to only a few venues: El Morocco and the Stork Club. A few big annual charity events, such as opening night at the Metropolitan Opera, were obligatory.

In the Eisenhower years the social order was dominated by corporations and white-collar lives. But the 1960s shook up everything sudden, surprising ways. A new generation looked at their parents' lives as boring and reeking of hypocrisy. They wanted out. Longtime social rituals fell apart. Young scions of wealth fled their parents' world, seeking new identities and new freedoms. Across the economic spectrum, people fended for themselves in a society without clear boundaries. It was exciting but frightening, for it was unclear where it was headed, what had been lost, and what would emerge.

Warhol was as much his own creation as any of his art. Born with a rounded nose, Warhol decided in June 1957 at the age of twenty-eight that his nose was so unattractive that he had to do something. He went to a surgeon not for a classic nose job, changing the shape of the nose, but a procedure that regrew the skin. Afterward, Warhol felt he looked better, but still did not believe he had an attractive face. It also did not help that he was so nearsighted that he stumbled around half-blind without glasses. Contact lenses solved that problem, but they were yet another thing he had to put on when he woke up in the morning.

Morning was also when he applied a thick coating of pancake makeup to cover up his blotchy, pale skin. The final touch was the toupee he glued onto his half-bald scalp. If one wore such a thing, he knew, there was no going halfway. Make it a glorious, thick mop of hair. Warhol kept changing colors on his toupee-one iteration of brown and blond after another-until he finally decided on the silver color that would by 1965 become part of his signature image.

The wig and makeup were the masks Warhol wore to greet the world. His public life was a continuing challenge. He sometimes struggled for words, but silence was the smarter move.

The crowd at the party kept getting bigger and bigger until people pressed up to each other, cheek by jowl. If a fire warden had come stomping in from the elevator, he likely would have sent half the people home. Many of the guests did not know Warhol. It was just another night out in the great, pulsating city.

Copyright © 2025 by Laurence Leamer. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.