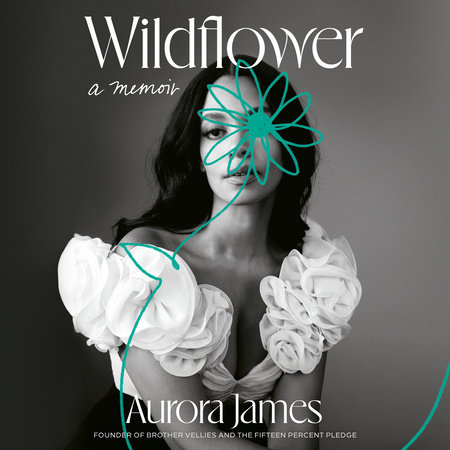

Why did I decide to write this book? I have always existed in a space of misconceptions—and while I’ve mostly not felt the need to explain myself, I’ve also come to understand the value of sharing my lived experience. Ultimately, the more we can understand one another, the better off we will be.

People think of me in a myriad of ways: The light-skinned woman with the nasally voice. The fashion girl from Canada. The founder of Brother Vellies, who won the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund. The designer who dressed AOC for the Met Gala in a gown that said “Tax the Rich.” The entrepreneur who launched the Fifteen Percent Pledge.

All of these things are true—but there are so many more parts of me. Some of my story may surprise you. Some may make total sense. Other moments might be hard to understand. But ultimately, all of these fragments pieced together make me, and all of us, human.

When I first launched the Fifteen Percent Pledge, I had no idea that it would take off to the extent it has. I thought it would get a little traction and that people would think it was a good idea. I hoped that maybe one person would be inspired by the idea and try to do it. I never expected that it would grow so quickly—or have such an incredible impact on Black businesses.

And yet, there have been many moments when I’ve almost given up. Other times when I’ve considered closing Brother Vellies, especially in the early days of the Pledge. Being under-resourced is something I am used to, but then add the staggering bias—both unconscious and not—working against me and Black women like me, and the effect can be defeating.

But launching the Pledge had nothing to do with what was easy. And yet, I felt that I had no choice. I’ve seen how talent and capability are distributed equally—while access and opportunity are not. Opening the door for those who have been historically excluded is not just the right thing to do, it is the first step forward in creating a more beautiful world for all of us.

I’ve thought a lot about the saying “Sometimes your best mode of transportation is a leap of faith.” It’s always deeply resonated with me, but it took me until this year to realize that for me, it was not my best mode; it was my only mode.

1When I think of my father, even now, I mostly see his back, him walking away. And yet, I can still smell his cologne, an Egyptian musk, and remember the thick woven African textiles he often wore. His accent was both singsongy and clipped at once. He was tall and had black, tightly coiled hair, cut short. His skin was dark brown and smooth to the touch.

He and my mother split up before I was born, so I never lived with him, but he did come visit. And throughout my childhood, he called every evening to remind me to brush my teeth. During one visit, I remember him teaching me how to moonwalk in my living room, Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal” blasting over our stereo.

Beyond these memories, I have no proof of his existence. No photo or piece of paper or article of clothing. I am not even sure what he was studying at college when my parents first met. These are the sorts of details my mother preferred to keep to herself.

“Why are you curious about that?” she’d ask. “How will it help establish your sense of self or destiny?”

I do know they were together until they weren’t. And that was when my mother discovered that she was pregnant. When he learned the news, he proposed getting married. She said, “No.”

When I asked why, many years later, she said, “He had too many patriarchal inclinations.”

To understand me, you must first understand my mother. She is brilliant and beautiful, with dark brown, thick, curly hair that glimmers the reddish hue of a manzanita tree in the sun. She has curious hazel eyes, a smattering of freckles, and stands five feet and five inches. Her weight often fluctuates within fifty pounds. I have rarely known her to shave her legs or armpits. She would consider doing so preposterous—unless one day, she did not. She is not a contrarian, but she does like to keep people guessing.

She was adopted as an infant and never knew anything about her biological parents. She once visited a woman who specialized in understanding people’s ancestry based on their facial structures. This woman deduced that my mother was Inuit and Irish, mainly because her cheekbones are so high set. This means I may be a mix of Inuit and Irish too.

Her parents, Hellen and Wesley James, raised her in Mississauga, Canada, just outside of Toronto. They chose her and her brother, also adopted, to create their family, which is also my family. But I am not entirely sure if my mother chose me. It feels more like I just happened. There is a difference.

At sixteen, my mother protested the Vietnam War, sang in a band, and left home to hitchhike across the United States with her much older boyfriend, whom she called the Silver Fox. They were headed to the Woodstock music festival, and as she tells the story, they took acid on Tuesdays, LSD on Fridays, and missed the concert due to a broken-down car.

She left again at the age of seventeen, this time for London, where she took up residence in a Kensington squat and learned how to blow glass. She claims that she was the first female stained-glass blower in England, and while I have no idea how to fact-check that, or what it signifies, I do know that she made all the glass prisms that hung in our garden. I called them the rainbow makers, because they turned droplets of water into sparkling Technicolor bursts that danced around the array of things my mother grew, from roses and rhubarb to carrots and coreopsis—and sometimes psilocybin (magic mushrooms).

In London my mother also learned to make her famous chili. To be part of the squat meant everyone took turns adding one ingredient, often stolen, to the communal pot that stayed simmering on the stove all day. An onion, carrot, or bell pepper. A bag of beans. My mother’s recipe has twenty-eight ingredients, one for each day in February, and is a dish that I make to this day.

My mother was in her mid-twenties and still living in London when her father died in a plane crash. He was an engineer for a Canadian royal commission that was creating a power-planning initiative for Ontario. He and eight others, including an indigenous chief, were flying in a Cessna on a research trip when their plane hit high-voltage wires while trying to land in bad weather. As a result, the Canadian government gave my grandmother a big chunk of money, which she subsequently used to take my mother on a trip around the world, to Morocco, India, and Japan, places that were all considered extremely exotic and foreign for Canadians in 1978. My mom and grandmother used this travel as an opportunity to get to know other cultures—and probably each other, as well.

Upon their return home, my mother decided to stay in Canada and go to university, which was where she met my father. She was going to call me Zoe, but then I entered the world still sound asleep, so she changed my name to Aurora, after Sleeping Beauty.

I spent my first six years in a tiny town called Guelph living with my mother and grandmother in a small, white bungalow. “Nanny” helped raise me. She had big, bright, clear blue eyes that were magnified by glasses, the size and shape of clear sand dollars, and wore silk blouses with big floral patterns tucked neatly into her slacks or skirt. She never left the house without her hair pressed and set, lipstick applied, and often wearing a fur coat. She even got me a mini fur that matched one of hers, which I wore over my taffeta dresses with Mary Janes and ankle socks to see The Nutcracker, our annual ritual. I thought I was chic before ever knowing what the word meant. “A man does not buy his wife fur to keep her warm, but to keep her pleasant,” was something Nanny often said. She was a woman from a different era, old-fashioned, and always kept a linen hankie in her coat pocket with a Werther’s butterscotch.

While Nanny defined “ladylike,” my mother’s style was textbook Bohemian. She preferred Indian earth-toned cotton skirts with drawstrings that ended in tiny brass bells and wore tube tops (without a bra). She almost always had fresh-cut flowers clipped in her hair and would leave a trail of sandalwood, frangipani, and spice wherever she went because Nag Champa was her go-to scent. Though every so often she’d add a spritz of a Dior perfume called Poison.

My mother worked as a landscape architect for Mississauga, the small city outside of Toronto where she had grown up. One of her jobs was to preserve and protect public trees. When my friend’s father, a developer, cut down a tree that was on city property, she was livid.

Copyright © 2023 by Aurora James. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.