Introduction“You are on native land.” Walking into the entrance of my restaurant in Minneapolis, Minnesota, you’re welcomed with a glowing red neon sign with those words. Inside the restaurant, you’re drawn to the beautiful view of the Mississippi River, the location of a once-mighty waterfall that in the Dakota language was called

Owamniyomni, roughly translating to “place of the falling swirling waters.” The waterfall is long gone, replaced by concrete skirting and a lock and dam, but the importance of the location still holds for those who know the history.

We named the restaurant Owamni to take back the original namesake of this special place, which has held significance for the Dakota community for centuries, long before the arrival of European colonists in the early 1800s. This restaurant was years in the making, and we couldn’t be prouder of creating something that not only showcases culturally important foods from Indigenous producers but also normalizes these health-sustaining foods. That was the early driving force behind my work—to help address the health issues plaguing our tribal communities, including high rates of diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. I realized we needed to return to a diet of the nourishing foods we ate before contact, which helped solidify my philosophy on decolonized cuisine. Reflecting that credo, our menu at Owamni is totally devoid of Eurocentric ingredients, such as dairy, wheat, cane sugar, beef, pork, and chicken. Eliminating these elements introduced during colonialism also meant that we would highlight the amazing and diverse Native foods of North America, and encourage guests to embrace their beauty as well.

But we aren’t cooking like it’s 1491. With dishes like cedar-braised duck tacos, antelope tartare with aronia berries, grilled sweet potatoes with maple chili crisp, and wild foraged teas, our team serves up delicious, nutritious, modern Indigenous food, proving to the world that it’s possible to run a successful restaurant without soda and ranch dressing. I’ve been told time and again how ambitious and innovative this mission is in the American restaurant world, but in my mind, we’re just doing what Indigenous peoples the world over have been doing since time immemorial.

When I look back on the journey that got me here, I understand I was always on this path. It just took me time in life to realize it. I was born on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota and am an enrolled member of the Oglala Lakota. When I was young, running wild across the grasslands with my sister and cousins, we had so much freedom. Like most kids in the ’80s, we had sparse parental supervision and were often left to our own mischief. I remember walking along miles of barbed-wire fence lines, dogs at our sides, darting redwing blackbirds on the fence posts. The occasional curlew flew overhead, making their presence known with their shrilling high-pitched calls, and curious prairie dogs ducked into their holes that dotted the landscape. We would spend hours outside in dusty cowboy boots, our imaginations the main source of our entertainment. The prairies smelled of dust, white sage, and nearby alfalfa fields. We rode horses, wandered through shelter belts of overgrown trees, and crossed wide open grasslands on foot, always coming up with ways to keep ourselves busy.

Because we lived on a ranch, dinner consisted of lots of beef, and we eventually ate our way through the whole animal. It was normal to have tongue, kidneys, and intestines in rotation for meals. There were no restaurants on Pine Ridge during those days. My grandparents had a cabin just off the Needles Highway in the Black Hills, where we spent many a summer playing in the creek, free-climbing rock walls, and just wandering. Growing up feral had its perks. We didn’t have a lot of money, but I wouldn’t change my childhood for anything.

After my folks split up and my mom moved us off the reservation, a new path started. Spearfish was a town of some seven thousand people in the northern Black Hills, about fifteen miles from the Wyoming border off I-90. My mom was going back to school at Black Hills State University (where I would later attend), and I was totally outside my comfort zone. I eventually found some friends and began the transition of living in a “big city.”

My life in restaurant kitchens started in Spearfish, where I got my first kitchen job at thirteen. The Sluice, as it was called, was a mining-themed American steakhouse with a mining cart salad bar. I learned quickly and continued to work in restaurants all through high school. When I was nineteen, I worked in Deadwood, South Dakota, where legalized gambling had brought hordes of tourists. I would start my day breaking down cases of whole beef tenderloins, cleaning the silver skins, portioning and bacon-wrapping them to an exact weight of five ounces. The restaurant had a $4.99 filet mignon special that came with a baked potato and a piece of Texas toast. After making a few hundred filet mignons, I would prep for dinner service.

I’d organize my station for the fury to come and pick out my music: the Black Sabbath album

Paranoid was my usual choice to get through the rush. Right before we opened, the seventeen-yearold dishwasher and I would step outside and take a couple hits off a one-hitter usually packed with low-grade Mexican brick weed that was always in my pocket back then. We went through about four hundred steak dinners a night, more on the weekends, and I was the only one running the flattop. I had a natural ability to move and learn fast, but at that point in life, I really didn’t have much exposure to good food. That would change with my next journey. After a bad truck accident that three of my friends and I were in, I got a settlement of $7,000, bought a crappy 1981 GMC pickup with mismatched doors, packed up everything I owned, and left South Dakota behind.

My first couple years in Minneapolis I lived paycheck to paycheck, leaning on cash from pawn shops to pay for food, gas, and beer. The only items I owned that had any value (and barely any at that) were a Yamaha acoustic guitar, a TV/VCR combo, and a Samsung boom box. I could usually borrow about $25 for one of those at the pawn shop down the street, whose owners I got to know pretty well. It would cost me about $35 to get them out, which I’d do on payday only to have them back in hock the next week. After a failed attempt at getting into art school (because I had no financial resources), I continued working in restaurants. Again, I wouldn’t change anything.

The scene in Minneapolis back in the late ’90s was really big for me at the time, with so many great musicians constantly coming through and artists having the freedom to be however weird they wanted to be. As I adjusted and started to find more friends, I got my first chance to be an executive chef at a small Spanish tapas restaurant (the first one in Minneapolis). I didn’t know anything about Spanish food, but I jumped on the opportunity. Because this was still before widespread Internet access, books were my main source of education. I began devouring cookbooks, but I couldn’t afford them so I would just sit at a bookstore in Uptown for hours learning about techniques, flipping through photos of dishes, and reading essays from the chefs in their own words. Rarely would I write anything down; mostly I just logged it in my memory to attempt later at work if the opportunity came up.

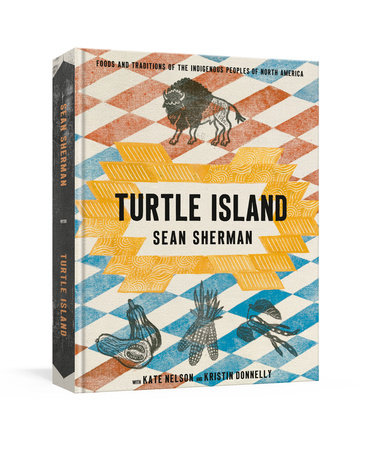

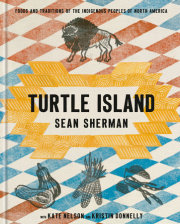

This hands-on self-education approach to the culinary arts was valuable, and I still love cookbooks to this day. That’s why after years of study and practice with Indigenous foods, I see it’s so necessary to create more resources about a topic that just didn’t exist in those days. I learned a lot about European foods back then, but never even had a notion to think about Native American foods.

Copyright © 2025 by Sean Sherman with Kate Nelson and Kristin Donnelly. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.