1

Nesting Sites

Where a bird determines to locate her nest is the key concern in establishing home territory. Oftentimes the nesting site may be inspired by natural boundaries-such as field, fen, shrub steppe, pond, or lake.

-G. Gordon's Field Guide to the Birds of the Pacific Northwest

$4

Mary Frances O'Neill was a young woman of many firsts. First in her graduate school class in the University of Washington's avian biology program, she was almost certain to graduate with honors. She was also the first female student in the history of Hood River Valley High School to earn a full ride to UW for academics and not sports. She was the first member of her family to complete a bachelor's degree, let alone a master of science. And she was also the first woman in the history of the family-O'Neill on her father's side and Healan on her mother's-to reach the advanced age of twenty-six without becoming a mother. This last, it should be noted, was not an accomplishment universally admired by her kin, many of whom wanted nothing more for her than a marriage with a nice local boy and a steady job at the county.

On this September day in 1998, Mary Frances, who almost everyone called Frankie, was not thinking about her academic, professional, or romantic future. She was focused entirely on getting to June Lake, where she hadn't been in more than a year.

The truck puttered along the Old BZ Highway north of the Columbia River, hugging the banks of the White Salmon River as it twisted and turned its way through the great dark woods. It was a difficult road, but Frankie knew it by heart-every curve and corner, each patch of rough pavement, and all the road signs, which grew fewer as the highway climbed up into the remote corner of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Here was the bridge at Husum Falls where flashing white water tumbled over the double drop into the river. There was the wide gray face of the dam that held back the once-wild flow of the White Salmon River. She knew which shoulders would be crowded with kayakers shuttling the whitewater run and which would be thick with fishermen casting from the sloping banks for fall steelhead. Then came fields stretching out on either side of the highway giving way to thickening woods as the road climbed toward the little jewel of an alpine lake tucked high in the forest at the foot of Mount Adams. Frankie cracked the window and listened to the rush of the river and the crash of the falls as she crossed the bridge. A kingfisher keened along the riverbank and a Steller's jay chattered a machine-gun reply. She'd driven this road countless times over the decades with her parents, her brother, her grandparents, and her cousins. This solo trip was a rarity and one she'd been looking forward to for months-clutching it like a lifeline, if she was being honest.

Her thoughts drifted as the trees flashed by, and she forced herself to think of practical concerns-the checklist of supplies she'd brought for her trip, the potential change in the weather during this transitional month of September, and the hour of sunset, which was the most important question of the day. Like most people who frequented June Lake, the O'Neill family never ran the boat after dark. Driving at night was to risk running aground in unseen shallows or colliding with old deadhead logs-remnants from the forest's timber heyday-that could surface unexpectedly. And even in summer, the weather could change quickly on the lake. Since the boat was the only way to reach the family cottage, it was a key consideration. Frankie glanced at her watch and at the sun now far above the west shoulder of the mountain. She had plenty of time. The knot of anxiety in her chest loosened a bit, and she leaned back against the cracked leather seat.

Traffic thinned north of the dam. A logging truck blew by trailing the sharp, sweet tang of freshly cut trees. After that she had the road to herself. It took more than an hour to reach Mill Three, and a light rain began to fall as she pulled into the marina parking lot.

Mill Three was one of several small logging towns unimaginatively named by the Cooley Lumber Company in the 1920s. The once-thriving settlement was now just a wide spot in the road with a gas station, a post office, and a shabby park next to a small marina where the O'Neills docked their boat. The communities of Mill One and Mill Two had long been reclaimed by the woods, and those who remembered them were all dead.

Frankie cut the engine and looked out over June Lake at a view that seemed unchanged in her more than twenty-five years of coming here. The dark green water caught the muted sunlight that slanted through the clouds and undulated without breaking. Large ponderosa pines and Douglas firs grew close together here all the way down to the water's edge. The empty halyard on the flagpole slapped in a nearly indiscernible breeze, and the weathered cedar docks rose and fell gently in the shifting water. A mourning dove cooed from within the branches of a big oak, and an osprey chirped sharply from its perch on a piling. Frankie climbed out of the truck and looked up the long, narrow lake. Mount Adams rose to the north with a ring of clouds circling its shoulders, heavy with new snow. Frankie zipped up her sweatshirt and turned toward the dock. The marina was almost empty this time of year, as most people pulled their boats after Labor Day. An old Century Raven bobbed gently against her lines in one slip. Someone, probably Patrick or maybe Hank, had repainted her name on the side, bright yellow against the black wooden hull. The Peggotty had been named by Grammy Genevieve, who'd been a great lover of Dickens and thought The Peggotty called to mind David Copperfield's unfussy, practical, and dependable heroine.

Only two other boats remained-a sleek Sea Ray and a battered red Hewescraft. The former belonged to one of the other families and the latter functioned as a water taxi and cargo boat. With no road access to the homes on June Lake, the summer residents were dependent on boats to haul people, food, and supplies up the long stretch of water. Some might have found the remoteness of the place an inconvenience. But for Frankie, June Lake had always been the calm center of the universe. It was a comfort to be back here where she felt most herself-a girl at home in the woods and falling in love with birds for the first time.

The sun struggled with the clouds, and the top of the mountain disappeared. The osprey chirped and then circled, dove, and snatched a fish from the water. Frankie shouldered her backpack and carried a load of boxes down the dock. She pulled the cover off the boat, and the Philippine mahogany decking gleamed in the low light of the cloudy afternoon. She smelled the faint scent of varnish and a knot rose in her throat. Refinishing the woodwork was a tedious annual undertaking that her father had always completed in fits and starts. She could picture him here, sanding, wiping the wood clean, brushing on varnish, and reading a tattered detective novel between coats. She dropped her gear in the boat and turned away from the image, returning to the truck to unload the rest of her supplies. In the boat she opened the faded red leather hatch to negotiate with the carburetor. The Peggotty could be cantankerous and hadn't been driven in months. Eventually the engine sputtered to life and the instrument panel on the dashboard lit up like a memory of Christmas. Frankie let the engine hum in neutral for a couple of minutes. She cast off and pulled away from the dock as the rain increased. The spattered windshield reflected her lanky frame and short dark hair. She pushed her bangs out of her face and flipped on the wipers.

Frankie's father, Jack O'Neill, had taught both of his kids to drive the summer Patrick was twelve and Frankie was eleven. She'd been thrilled about the prospect of getting behind the wheel, though Patrick hadn't seemed to care much. When his lesson was over, he went back to his stool in the dock store and the book he'd been reading. But it was different for Frankie. She could recall every detail-the feel of the polished wheel under her hands and the timbre of her father's voice as he explained the function of each dial on the instrument panel. He showed her how to affix the navigation lights and how to change the wiper blades. How to gas up, where to add oil and coolant. He demonstrated the art of drifting the boat in neutral, forward, and reverse. How to gauge the effect of the wind when landing and leaving the dock. He explained right-of-way, safety, and man-overboard scenarios. He quizzed her until he was satisfied and then put the keys in her hands. Frankie adjusted the choke, turned the key, and coaxed the engine into a stuttering neutral. "Gotta be patient with the gal," Jack had said. "She's older than your old man."

That day Frankie pulled away from the dock and puttered toward the center of the lake. Once she was clear of the log boom, her father nodded at her, and she eased the throttle forward. She watched the bow plow through the liquid green and accelerated until the boat came to plane. "That's my girl!" Jack yelled over the sound of the engine. He settled into the passenger seat and put his feet up. After that, Frankie became the de facto driver of the family, which suited her just fine. It was Frankie who ran her dad back and forth to the marina. Frankie who picked up supplies in Mill Three for Grammy Genevieve's store. Occasionally she drove other residents down the lake when the water taxi wasn't available or picked up their friends at the marina. They gave her big tips, but she would have driven for free.

Her love for the old boat had never left her. Now, in the increasing rain, she felt her heart lift as The Peggotty cut through the water at medium throttle. If it wasn't exactly joy she felt, it was a lightness compared to the weight on her chest, the tangled mess of feelings she'd been carrying around for months.

The trip from the marina to the north end of the lake took nearly two hours. The water was fast and flat, and Frankie leaned back, steering with one hand. She took the middle channel, watching for deadheads and other debris that came down off the mountain with fall rains. The breeze carried the clean scent of water and evergreen, damp earth, and woodsmoke and blew her hair around her face. She gazed at the high cliff line along the east side of the lake, which marked the boundary of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. When she passed Arrow Point at the halfway mark, she noted the still waters of the small cove there. The blue light of the glacier on Mount Adams glinted in the rain, and the Windy River was a thread of white tumbling down the south chute of the mountain. She slowed at a large tree-covered headland that shouldered its way out into the lake. Rounding the corner into the sheltered cove of Beauty Bay, Frankie felt her heart crack wide open as the houses came into view. The ten Cape Cod-style cottages retained the genteel charm of the 1930s, when they'd been built. Painted in soft hues of blue, green, and yellow, the cluster of houses looked like a toy village from a distance. The summer homes had been owned by the same families for generations and maintained in their original style. The houses and the sandy beach were separated by a long, elegant stone seawall that had been built by Italian masons lured away from the WPA program building Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood. Green lawns ran from the seawall to the porch of each house. It was the perfect spot for the clutch of summer homes, but it was also the only location that would have worked on June Lake. The south bank belonged to the unincorporated community of Mill Three. The sheer cliff of the west shoreline was impossible to build on, and the eastern side belonged to the Yakama Nation.

In the 1960s, the Magnusen family, newspaper scions of Seattle, had made noise about wanting to build something more modern but had never followed through. None of the other families saw fit to change anything. So as the years passed, the houses, their wooden docks, and the elegant stone seawall endured. The trees grew tall and broad. With no automobile traffic, the birds and wild creatures flourished here.

The O'Neill family, scions of nothing, had gained a foothold at June Lake thanks to the mysterious machinations of Frankie's grandfather, Ray O'Neill. Ray had emigrated to America in the 1930s along with thousands of Irish who'd crossed the Atlantic looking for a better future. Her devilish grandfather, with his sunny disposition and gift of gab, had landed in Hood River and talked his way into a job as an errand boy for Charles Stevenson, the local timber baron. On the Stevenson payroll, armed with his bright blue eyes and genuine love of people, he charmed everyone from the town housewives to the gruffest of lumberjacks and the small coterie of businessmen who controlled the then wild corner of Oregon. And if they didn't like his stories and jokes, those men appreciated Ray's talent for procuring the best Canadian whiskey during Prohibition. When Prohibition ended, Ray opened the River City Saloon in Hood River. The thirsty lumberjacks and rivermen patronized the tavern along with local law enforcement, who'd always been among his best customers.

The origins of the cottage were murkier. Ray never confided the full story, not even to his wife, Genevieve, but it had something to do with a backroom poker game with the developer of the Beauty Bay Resort, which had gone from investment scheme to full-blown boondoggle and eventually resulted in the construction of these few summer homes along the lakeshore.

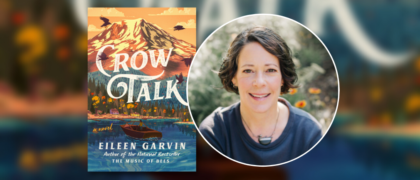

Copyright © 2024 by Eileen Garvin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.