Bald-headed cabbage patch

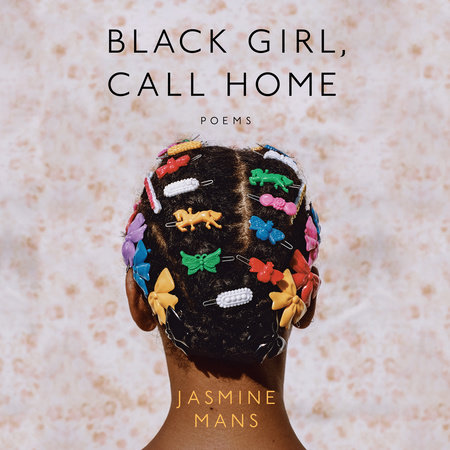

ain't got no hair in the back.

Bald-headed skittle diddle

ain't got no hair in the middle

I Ain't Gon' Be Bald-Headed No More

I wore these braids for two

whoooole months, and tonight

Momma gonna wash my hair

when she gets off work at 7 p.m.

It's longer than it was before,

and when I wear it out at school,

the rest of the girls

won't call me bald-headed

no more.

Imma be pretty,

as soon as momma gets home

from work.

Momma Has a Hair Salon in the Kitchen

Wash

Barrettes

Twists

Crisscross

Braids

Beads

Cornrows

Wooden brush

Edges

Silk scarf

Nappy

Kitchen

Beady beads

4c

Coil

Ouch

SuperGrow

Straighten

Burn

Breakage

Drip dry

Split

Crunch

Grow

Cut

4a

Yakky

Bundle

Bleach

Chop

Short

Dye

Curl

Slick

toothbrush

Damage

Afro

Roller set

Shrinking

Ugly

Long

Thin

Thinning

Thinner

Weave

Heat

Press

Hot comb

No edges

Toothbrush

Nigga naps

Sheen

Spritz

Dryer

"Hold ya head still!"

Deep conditioning

Pretty

Bleach

Vaseline

Shrunk

Burn

Breakage

"Don't make me pop you!"

Scalp

Fine

Just For Me

Poison

Natural

Pressed

Dry

Damage

Edges

Trim

"Be still"

"Hold your ear."

Momma prays

like she's talking over God,

and if God were to talk back

she wouldn't even hear Him.

That Was Her Way of Showing God

We didn't go to church on Sundays,

but my mother cleaned

the whole house.

Wiped from behind the toilet-

to inside of the oven.

That was her way

of honoring God.

Separating cloth

by color,

making sure

nothing bled,

onto anything else,

stretching pork

across seven days,

because even poverty

knows ritual.

Baptizing Black babies

in bathtubs

of hand-me-down water,

one, after

another.

A poor woman's tradition,

but of its own abundance.

That was her way of showing God

that she had a servant's heart,

that she was a good woman,

with all of the little

she had.

Macaroni and Cheese

"Macaroni and cheese,"

my mother says,

". . . is all about pattern,"

and how well

you can harden the edges

without burning them.

Ma could count a teaspoon

with the lines on her palms,

could measure an ocean

and tell you how long it would take

to bring it to a slow boil.

She'd say

the women in our family

grated their own cheeses

bought their greens fresh

from the harvest farm,

and made sure the babies ate them

for a good bowel movement.

She wouldn't let us lick

the whole batter,

but gave us the spoon.

She could remember Easter

when the rest of the family

forgot God.

She'd say

"You'll sit there until

you finish your plate."

Thought waste was the worst sin.

Told us about all the starving kids

in Africa who'd give anything

for her meat loaf.

She didn't let things go bad.

She didn't let anything spoil

in her refrigerator.

I know grace and mercy was raised

by the same single mother.

We Host These Variables

We try to leverage language as a means to a truth. We learn, on our paths, perhaps, that certain stories have no language, nor require one. There's something I want to honor here. I want to honor the silent story, the emotions unaccompanied by human language. I want to honor the weight of the stillness. I want to honor the silent ceremony between mother and daughter. A ceremony of blood and becoming. Because, I know, we exist with a heavy and stubborn resemblance. I know the distance between mother and daughter. How we are many burned bridges, as well as, a wealth of brick and clay, ready to be made anew from everything unmade of us. I am learning my mother's song, staring into her silence, as it stares back at me. Wondering of its depth, and wandering through it. I don't know all of her pain, or if it can be held with two hands. But she looks back at me, with girlish eyes, wanting to be remembered for something I do not recognize her as. Daughters have questions for their mothers, questions made up of no words; we host these variables. A woman stretched her body for me, and I have no words to describe her in wholeness, but without shame, I want you to know her. My mother.

Speak to Me of My Mother, Who Was She

Tell me about the girl

my mother was,

before she traded in

all her girl

to be my mother.

What did she smell like?

How many friends did she have,

before she had no room?

Before I took up so much

space in her prayers,

who did she pray for?

B'Nai's Three Babies

B'Nai had three children

C-sections with all three

two boys and one girl.

Each of them

would've stayed inside her

and she would've let them

because she loved them babies

that kinda way.

They gave her gas,

chest pains,

and sat right on her bladder,

but they were her babies.

Antione was the first,

the one that would usher her

into motherhood.

He was the baby

that made Tyrone

marry B'Nai.

The one she'd dress up

and flaunt around.

The baby that every aunty

had a naked picture of.

He was the baby

that got Aunty

off drugs. She tells

folks that God sent

Antione to save her,

and she let him.

Jasmine was the second baby,

delivered in St. Michael's Hospital,

screamed when she was born

like all babies do, but didn't stop,

a colic baby.

Cried like she already knew

how much pain

the world had in it.

Jasmine sent B'Nai

into a tired depression.

She gave up sleep

for that little girl,

and her job at the bank.

Said that she didn't have time

to make anything else

of her hands, but cradle.

Sometimes the neighbors

would come over

and hold the baby.

These women knew

what it was like

to have three babies,

a working husband,

and to be left all alone

with the smallness.

LT was the last baby,

named after Tyrone,

the one they couldn't afford,

and truthfully,

they couldn't afford any of them.

Tyrone got his second job

when LT was born,

worked all seven days

out of the week,

because that's what men

are supposed to do.

LT was the biggest

and still is,

weighed ten pounds,

when he was born.

B'Nai's favorite baby,

the one that loves his momma,

has his nana's eyes,

a happy baby.

The one

she fed turkey legs,

and pork bacon to.

The baby that sucked the chicken bone.

The one she'd hold on to

the longest.

The lightest, and most sensitive

out of the three.

There were three babies,

and a woman stumbling

into motherhood.

No money,

and an apartment

in Newark.

She learned how to cook

with those children,

learned what spaghetti

and meat loaf could do.

She prayed to God

for her babies

that they'd learn

the vocabulary

she didn't have.

Prayed to God,

for him to spare her three

Black babies, when the plague came.

Because she was their momma,

and she was gonna do right

by each of them.

Period

Mothers teach their daughters

how to hide the blood,

how to wash out the stains upon arrival.

To pretend like the blood isn't there, or theirs.

Mothers teach their daughters

to make sure the blood doesn't have an odor.

To never let the stench rise.

Mothers teach their daughters

to be misleading about the amount

of blood. And the weight it adds to the body.

Mothers teach their daughters to never bleed

out. To not use the blood as an excuse, even

when the blood

is the only

excuse.

I resent my mother

for things she has sacrificed

on my behalf.

Treat Her Right, While She's Still Here

When I hang up

on my mother,

Sabrina says,

"Must be nice."

"I never had a mother

to hang up on.

I wasn't old enough

to have a cell phone,

or an attitude,

when my mother died."

Before my mother knew

I was a lesbian,

She prepared me

to be a man's wife.

Momma Said Dyke at the Kitchen Table

Momma said,

so you gonna be a dyke now?

As if she meant to say,

didn't I raise you better than that,

don't you know

I ain't raise no dyke,

don't you know

you too pretty to be a dyke?

Why you gonna embarrass us like this,

you scared no man gonna love you,

you scared of men,

some mannnnnnn hurt you,

who hurt you?

Momma said,

so you gonna be a dyke now?

As if she meant to say,

don't you know

how hard it already is

for women like us,

why you gonna go

and make it harder on yourself?

I don't want you in that kind of pain,

this world ain't sweet on those kinds of women,

I don't want another reason to be scared for you.

Momma said,

so you gonna be a dyke now?

As if she meant to say,

I'm scared for you.

The First Time the Black Girl Calls Her Mother a Bitch

This is the moment

the Black girl unmothers herself,

when she refers to her momma

as bitch, and the word

settles in her mouth,

like a razor under

her childish tongue.

She will run away wearing

her womanhood, like a loose pair

of heels. Her breasts will sit up higher

than they were.

She will stand nosey

and act bigger than herself.

In this part of the story

she doesn't have a mother,

But she does,

she always will.

Grits: 1967

Nana's kitchen

is as old as the Civil Rights Movement,

sometimes she can't remember

which came first,

the grits,

or the riots.

Birmingham

Momma said the bomb

wasn't meant for me.

I think it was meant for Pastor Martin

because he be havin' them dreams.

Maybe those white men didn't know

that little Black girls

we be goin' to church too,

and we be foldin' our hands,

praying and we be taking communion

just like their daughters do.

Maybe if I wore my church shoes

the bad men would've never came for me.

I knew they matched my dress

but they always just be hurtin' my feet.

I be thinkin', did God christen the bombs

that exploded my flesh into sacrifice?

And do anybody be hearin'

those sacrificial scriptures,

spoken in tongues,

claiming Christ,

before everything went boom?

Before the smoke

and rubble

baptized these collapsing bones?

Maybe if they knew,

we were like the most beautiful flowers,

right before the wind and dirt

began playing tug-of-war

with the delicates

of our petals.

Momma said,

it only took one man

to die for the sins

of this entire world,

so how did that man

let this church tremble

on my soul?

And I don't remember

there being enough holy water

to stop the smoke,

or to calm the burning.

Momma said,

some heartbreaks just be too hard

to swallow at communion,

some serpents

just be finding salvation

in baptismal pools,

some church mice

just be screaming

America's dirty little secrets.

Momma said

some deaths,

just be too black,

and too white

to be labeled holy,

Some sacrifice comes without permission,

Some sacrifice comes without fair warning,

God can't always protect you

from the boogie man,

so some baby girls will reach the pearly gates

and won't be tall enough to turn the handle.

Momma said,

some men . . .

some men

will just be too guilty to claim innocence

with their own Christ.

But what did . . . what did I do?

I never wanted to play with the white girls.

I-I never asked for integration;

I wanted roller skates-

an extra piece of cake, after dinnertime.

Sometimes I just be thinking,

maybe God was too busy

trying to protect Martin

to think about us,

I ain't never ask

for that man's dream.

But momma . . .

momma be sayin'

that his dream

just been askin'

for me.

South 14th Street:

Nana's House Smells like Cigarettes

Nana's house still smells

like cigarettes.

Today,

Nana got open heart surgery

she still drinks Pepsis,

she still smokes,

she's still strong.

But her heart

don't trust her,

well,

not like it used to.

Nana smells like Newports,

it reminds us

that things caught smoke,

but never did they catch fire.

South 14th Street: The Attic Window

From Waiting

My grandfather died

in bed with my nana.

She said she saw

His soul soar

right out of their attic window.

He left his body

in that bed to remind her,

that even without breath

she could still wake up

to him.

She said, he left silently

didn't want to wake her up

out her sleep as he got ready

to leave.

Kissed her on the cheek,

gathered himself

at the foot of the bed

and didn't take anything

with him,

not even her smile.

South 14th Street: For Sale

Nana is selling the house,

the one on South 14th Street,

off of Clinton Ave.

The house she was married in,

the olive house

with the hunter green trim,

the house with the uneven

driveway, that skins the chin

of every car that tries to pull up,

even the nice ones.

The wood is just rotten, the pipes

need replacing, and Nana, she's just too old

to maintain it all. The neighbors

ain't like they were back in the day.

Things have changed

since poppa died,

and it's different

without no one 'round

to take out the trash

and to shovel

the steps.

At Aunt Kawee's House in Oklahoma

She woke up out of her

sleep, saw them, and

yelled to those angels

from the bottom of her

throat!

"get away from that bed!"

And those angels left,

empty-handed,

they left.

"And her voice was a drowning piano."

Blame

I blame my father

for things he cannot control.

I blame my father

for things he can control

but chooses not to.

I've seen my mother

with a broken heart

before.

I blame my father

for all of my mother's

broken hearts.

The Thing That Made Him My Father

I've never seen my father cry,

or speak of his mother's death.

He doesn't talk about his brother,

the one that passed away.

He doesn't talk

about what he remembers

of his first father,

or his second.

He doesn't speak of the story

that made him my father,

or a man.

Because I Am a Woman Now

Nana may have cancer,

and I'm looking for my mother

to tell me that it'll be okay,

that there is no such thing as cancer,

that Nana is stronger than cancer,

that cancer has no place in our family,

or in her body, that we know prayers stronger

than cancer. But she won't say those things

because I am a woman now,

So she says . . .

"We'll see,

we don't know,

but we'll see."

Nana's heart sits between two cancers.

The left and right lung.

I have reason to believe

Copyright © 2021 by Jasmine Mans. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.