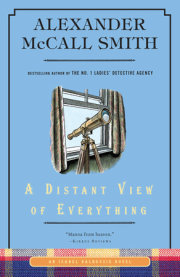

Chapter OneCarbolic Soap and Birthday CakePrecious Ramotswe, daughter of the late Obed Ramotswe of Mochudi, near Gaborone, in Botswana, near Heaven, wife of Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni, garagiste; friend to so many, but particularly to Mma Silvia Potokwane, and of course Grace Makutsi, formerly of Bobonong, who was, in turn, wife of Mr. Phuti Radiphuti and a graduate of the Botswana Secretarial College—with ninety-seven per cent in the final examinations; that Precious Ramotswe lay in her bed, opening first one eye, then the other, and subsequently, after only a few short seconds, closing both once more.

Waking up in the morning, as she had now done, was never too difficult; the hard part, she always thought, was what happened afterwards. To begin with, you had to remind yourself where you were. Those first few seconds of consciousness could be quite detached from everything else. You knew who you were, of course, and you knew you were in your bed, but you did not necessarily remember where you had just been: there might still be drifting around a few fragments of a dream, the remnants of some curious and unreal events in which the sleeping you had just been participating, and you had to put those out of your mind as the real day began. The mind was good at that—it remembered not to remember, so to speak, because it knew that dreams could not be allowed to clog up memory, which had far more important things to do. And so, the strange conversations of the night, the odd transports back to childhood, the unlikely dramas and surprises—all these were swept away as the light of day signalled the beginning of your real life, as yourself, facing another day of being you.

Now, on that particular morning, Mma Ramotswe was fully awake, and conscious of the fact that she was alone in her bed, and that her husband was no longer there. You could always tell when there was somebody else in bed with you, and, equally, when there was not. There was the silence, of course—there was the absence of the breathing noises that husbands tended to make—and then there was something about the way the mattress sloped when there was nobody to counteract the weight on one’s own side. And then, if you turned in your bed, as she now did, you saw that there was nobody there, and you began to listen for sounds from deeper within the house. For the sound of your husband in the kitchen, for example, preparing breakfast in bed for you as a treat, because today, you suddenly remembered, was a somewhat special day, being your birthday, when breakfast in bed—or even a simple cup of red bush tea placed steaming on the bedside table—would be so welcome. Not that you expected it as your right, but it would still be a nice touch.

She listened hard, holding her breath for a few moments so as to hear better, but there was no sound coming from the direction of the kitchen. And there was nothing to be heard from the other two bedrooms, because it was that odd, quiet time of the year, the school holidays, when the children were away for three weeks. They were staying in Lobatse with the families of schoolfriends, helping with the planting and the cattle, and learning to love the land, which is something we all should learn to do when we are young. No, the house was quite silent, and that meant that Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni had already gone off to the garage, as he sometimes did when there was a lot to do and rather too many cars waiting for attention, like a line of patients nursing their complaints in a hospital waiting room.

Mma Ramotswe sighed. You should not begin your birthday with a sigh, though, and she quickly turned the sigh into a deep breath, the sort of breath you take when you are deciding to be positive about the day ahead. She then put on her housecoat and slippers, and made her way into the kitchen to fill the kettle. As she entered the room, her eye fell on a note displayed prominently on the table, and she smiled. That would be the message he had left for her, saying something like, Happy birthday, my dearest wife— I am so sorry that I have had to go to work early on this special day, but I’ll make up for it later. Your loving husband, Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni. Something like that.

She picked up the note and read it. Gone to work, it said, rather tersely. See you at tea time. Don’t forget to buy soap for the garage, please. The please was underlined—not out of politeness, but to emphasise the importance of the request. And that was all. There was nothing about her birthday—just that reminder about the soap that he needed for the washbasin in the garage so that he and his assistant, Fanwell, could get the grease off their hands after attending to engines and before handling the upholstered steering wheels of the cars in their care. Soap was important, she thought, but so were birthdays—and if one had to rank the two things in order of importance, she would say that from the point of view of the person whose birthday it was, birthdays outranked soap.

She made a conscious effort not to feel upset. Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni stood out for his politeness, even in a country like Botswana, where people were naturally courteous towards one another. He was not one to use cross words, nor did he ever forget the traditional decencies—the formal greetings and enquiries about whether you have slept well, and whether your family have slept well, that sort of thing, which had always been observed in Botswana but were under threat, as such things were under threat everywhere, throughout the world. And there was another thing: he never raised his voice and not once had she heard him swear. Nowadays people swore with very little provocation, using language that, when she had been at school in Mochudi, would have brought the wrath of the authorities down upon one’s head. She vividly remembered the day when a boy in her class at school—a boy of eleven or twelve, who had a reputation for being short-tempered—had used bad language within the hearing of one of the teachers. He had imagined that nobody could hear him, or at least no adult, but he had been wrong, and he had been picked up by the scruff of his neck and taken to the boys’ washroom, where his mouth had been washed out with Lifebuoy red carbolic soap. He had howled in protest, as that soap was known for its sting, but he had not sworn again, in the schoolyard, at least.

She had told Mma Makutsi about that incident, and Mma Makutsi had nodded and said, “Quite right, Mma. That’s the way to do these things.”

Mma Ramotswe had expressed reservations. “That was the way they used to do things, Mma. I’m not sure you can do that sort of thing these days.”

Mma Makutsi looked at her incredulously. “That’s ridiculous, Mma. Why not?”

“I think it’s to do with rights,” Mma Ramotswe explained. “People have more rights these days, Mma.”

Mma Makutsi’s look of incredulity turned to one of dismissal. “Rights, Mma? Even children? Even boys like that foul-mouthed boy you mentioned?”

“I think everybody has rights now,” said Mma Ramotswe.

Mma Makutsi shook her head. “Children need to be told what to do, Mma. You cannot let them run round without being told what they can do and what they can’t do.”

“Oh, that’s true, Mma,” Mma Ramotswe conceded. “Children have to be disciplined.”

“Well then,” snorted Mma Makutsi. “How do you discipline a child who’s using rude language? You tell me, Mma. You tell me. How do you discipline a boy like that? You wash his mouth out with carbolic soap—that’s what you do. And if he starts shouting about his rights, you say, ‘And we have a right not to listen to you speaking like that, young man!’ That’s what you say.”

Mma Ramotswe said nothing. She thought that Mma Makutsi had probably not taken her point about how the climate of opinion had changed, and the old ways of punishing children for their transgressions had been discredited. You were not meant to slap children these days, and you certainly weren’t meant to beat them in the way in which children used to be beaten, even in living memory. You spoke to them sharply; you told them of the consequences of their actions for others; you reasoned with them. And she was pleased with these changes, because violence merely begat violence, as everybody knew now—or should know, even if they had yet to learn that.

But Mma Makutsi, who, in spite of her more modern clothes, was still rather more old-fashioned than Mma Ramotswe in these matters, now had more to say on the subject.

“In fact, Mma Ramotswe,” she continued, “I can think of quite a few people who would benefit from having their mouths washed out with carbolic soap. Adults, this time—people who use very bad language in front of other people. They don’t seem to care. They use these words as if they don’t mean anything.” She paused. “That man who works in the supermarket—you know the one? He’s always shouting at his staff and using very rude language. They’re too frightened of him to tell him not to shout so much—or to call them the names he calls them, which he certainly should not do. They should do that—they should stand up to him—but they don’t. That’s one man who would benefit from a bit of carbolic soap, Mma.”

Mma Ramotswe inclined her head. She knew the man Mma Makutsi was referring to, and she smiled as she thought of how outraged he would look if somebody were to manage to wash his mouth out with soap. It was a lovely thought—a bully dealt with by the very people he had bullied, which was always something nice to contemplate. And, Mma Makutsi was right about the carelessness of some people, about the lack of respect for the feelings of others, and for decency, but once again she did not imagine that a programme of washing people’s mouths out with soap would help very much. And so, she said nothing, and Mma Makutsi, feeling that she had won the argument—if it had been an argument—looked satisfied, as people who have made their point forcibly may look.

Now, standing in her house in Zebra Drive, Mma Ramotswe thought of Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni’s mildness and how he would never intentionally upset anybody, particularly her. He loved her with all his heart—he had once told her as much, in a rare moment of self-reference—and she, of course, reciprocated. He was proud of her—she knew that because Mma Potokwane had once told her about what he had said about his good fortune at being married to her. So, if now he appeared to be ignoring her birthday and had written a note that seemed a bit curt, that was probably because he had a lot on his mind.

She was in no doubt that he had simply forgotten her birthday. Now that she cast her mind back over the previous few days, she realised that she herself seemed to have forgotten that her birthday was coming up. She had not thought about it at all earlier on in the week, and it was only yesterday that she had reminded herself that the following day was the day in question. Had she said something to Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni at that point, then he would undoubtedly have remembered—but she had not, and this was the result. So, she could hardly blame him for the omission: forgetting to do something did not involve any intention to harm—it was something that happened to you, rather than something you decided to do. And there was a difference between those two things, she thought.

And there was something else to bear in mind: Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni was a man, and men, by and large, did not remember birthdays as well as women did. That was not to run men down unfairly—Mma Ramotswe would never do that—but you had to admit that men had their drawbacks, just as women did, and one of the failings of men was a lack of inclination to remember birthdays. Women, by contrast, remembered the birthdays of their friends, and often of their friends’ parents or children. Mma Ramotswe remembered Mma Potokwane’s birthday, because it was the day after the birthday of the late Seretse Khama. But she also remembered the birthdays of at least two of the housemothers at the Orphan Farm, and those had no important dates attached to them.

The first of July, 1921: that had been when Sir Seretse Goitsebeng Maphiri Khama had been born—a day of the utmost importance for Botswana. He was the grandson of Khama III the Good, and had become, in his time, the Paramount Chief of the Bamangwato people; and then, on that windy night in 1966, when the Bechuanaland Protectorate was laid to rest, first president of a brand-new country. Mma Ramotswe’s father, Obed Ramotswe, had admired him greatly, and had even met him once—something of which he had been so proud. And she, in turn, was so proud of her father, so proud; and not a day went past that she didn’t think of him and of what he had stood for. And her mother, too, who had died when she was so young, but who must have been a fine woman, because that was how her father described his wife, and he was never wrong about that sort of thing. Mma Ramotswe was proud of her, too, and wished that she had known her. Not to know your mother left a big hole in your life, but then . . . She stopped herself. Everybody had holes of one sort or another in their lives, and you should not spend too much time thinking about what you lacked. You should think, rather, of what you had, and she had so much—this house, this wonderful, if occasionally forgetful, husband; these kind friends, even if Mma Makutsi could occasionally be a bit sharp and Mma Potokwane was sometimes a bit pushy; the children, whom they had fostered, but who were like their own children now; her business; her country, that great beautiful stretch of Africa—there was so much to be grateful for.

Copyright © 2023 by Alexander McCall Smith. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.