Chapter One

December 1992

I still dance in my dreams.

But not in my life. In my life, I shuffle around this too-large house, tossing whatever is within reach into the nearest cardboard box, not bothering to wrap anything in newspaper or to make sure the box labeled living room actually contains items from the living room.

The movers are far more worried about my belongings than I am. As I've hit my fifties, I've found that the stuff that surrounds me every day has lost its charm. Like the clock on the fireplace mantel that I pick up, surprised at its heft. The darn thing hasn't worked in a decade. Or the cast-iron Le Creuset pot that sits in a drawer doing absolutely nothing. I haven't given a dinner party in ages, and I'm not about to start now. Some people end up hoarding their possessions, unable to get rid of the plastic bags that the groceries came in, but that's not me. To be honest, I'm getting a kick out of seeing box after box go out the door, like a snake shedding its skin. Out the door and into the big truck, to be dropped off at the Salvation Army. The few pieces that are left, including my antique bed and my favorite armchair, will be delivered to a sunny one-bedroom with high ceilings in Sutton Gardens, an independent-living community for the fifty-five-and-over set, where you can mind your own business in the comfort of your room or join in on a water-aerobics class, depending on the day.

You would think that after independent living comes dependent living, but instead it's "assisted," which brings to mind someone delicately holding your elbow as you cross the street in the best of circumstances or offering extra leverage as you rise from the commode in the worst. Having been the assistant myself for many years, I know full well what's involved. Finally, there's the memory-care floor, which is a laugh because for most folks behind those locked doors, there aren't that many memories left to be careful about.

That's not me, though. Not by a long shot. At fifty-five, I still have all my memories intact, thank you very much. There are days when I wouldn't mind blocking out the more painful ones, but I have nothing to complain about, not yet. I'm aware of my limitations, but I'm not defined by them.

My new lodgings are just down the road from this house, so I'm not venturing very far. Even though Bronxville is only eighteen miles from Midtown Manhattan, it's an oasis of green, renowned for its "stockbroker Tudor" houses, the term coined after the newly rich who snapped them up in the 1920s and '30s. People like my father, who was looking for a home that was close to the city but not too close, a place that showed he had good taste and a good job. My father never got tired of pointing out the slate roof and lead glass windows to visitors. He may not have been a stockbroker, but he was a company man and proud of it.

I look about my living room, almost expecting to see him drinking a scotch in his favorite armchair, and my throat tightens.

"Let me help you with that."

One of the movers, a skinny kid with freckles whom the others have teased all afternoon, puts the box he was carrying on the coffee table and comes toward me, eyes wide. He gently takes the clock from my hands.

"It doesn't work," I say, wiping the dust from my palms. "You can have it, if you like. Maybe it can be fixed."

"We're not allowed to take anything," he says. "But thanks."

He looks like he's barely sixteen and is more tentative in his actions than his cohorts, who move about the house like they own it. "You're new at this," I say.

"It's my first day."

"That's why they're making you do all the hard work, like climbing up into the attic. You better not take that kind of guff from them. They'll never stop."

"I don't mind." He pauses. "I found some things in the attic that I thought you might want to sift through, maybe give a last look."

I wave my hand. "No one's been up there in decades-whatever it is, I don't need it."

He turns to the large box sitting on the coffee table and opens it. "Well, this almost split open when I was upstairs. I'll have to take everything out and tape up the bottom anyway." He lifts out a pair of pointe shoes from when I took ballet class as a teenager, the ribbons fluttering loose like silk ringlets. "You were a dancer?"

I wish I had taken a moment, just one moment, back when I was dancing, to stop and appreciate what it felt like to lift my leg effortlessly high, what it was like when my limbs and mind were rich with music and my body snapped into place. When my arms and legs did exactly what I told them to do. In my dreams, I stretch like a rubber band and my body is nineteen again. And then I wake up stiff and sore and realize it's only getting worse.

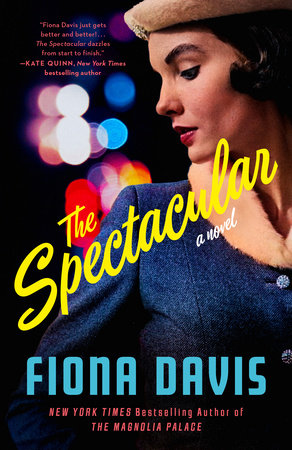

He places the shoes carefully on the coffee table, as if they were made of glass. Reaching back into the box, he pulls out a program for the Radio City Music Hall Christmas Spectacular of 1956. Then a pair of worn Capezio character shoes. I remember exactly what it felt like to buckle them up and dash out of the dressing room, how they eventually molded to my feet after hours dancing onstage. When I see those shoes, the voices of the other dancers fill my ears, along with the strains of the orchestra warming up.

But some memories are not as welcome. Screams of fear, the smell of smoke. Bloodstains on my dance tights, a lone red ribbon.

A combination of terror and regret wraps around me like a straitjacket.

The boy is about to dig deeper, but I stop him. "Enough."

The doorbell rings and I leave him so I can answer it. He can decide what to do with that box. I don't want it.

A young girl with raindrops in her hair stands on my porch.

"Yes?" I ask.

"Ms. Brooks? I'm Piper Grace Cole. You can call me Piper. I'm here to pick you up."

"For what?"

She blinks. "Um. The Radio City Music Hall anniversary? It starts at seven p.m. Sorry I'm early, I didn't want us to run into rush hour traffic." Behind her, a black sedan with a driver sits idling at the curb.

The Rockette alumni group is always sending me newsletters with chipper reports of grandchildren and moves to Florida. I usually give it a quick scan for any familiar names and then toss it in the bin. I don't remember ever saying that I'd attend the anniversary celebration.

"Do you mind if I come in?" Piper asks. The wind has picked up and the rain is getting both of us wet now.

I let her inside and she follows me to the kitchen. There, on the refrigerator, is the invitation, held in place with a small magnet: Radio City Music Hall Invites You to the 60th Anniversary of the Rockettes. A couple of weeks ago a woman had called to confirm I was coming. Ann Burris was her name. I'd said I couldn't because I don't drive or take the train anymore. She'd told me she'd take care of that, and apparently Piper was the result.

"Are you a Rockette?" I ask.

"Gosh, no." She says it with a rush of air, as if I'd asked if she were the Queen of England. "I'm an assistant to the events coordinator, Ms. Burris. I was told that you were precious cargo and to make sure you made it to the theater in one piece."

"Precious cargo." What a strange phrase. "I'm sorry to make you come all this way, but it's not a good day. I'm moving, you see."

"Oh." Her face is crestfallen. "Ms. Burris will be very upset. She'll think I did or said something wrong." She digs into her bag, hands shaking. "I brought the program for you, so you can see that it's going to be terrific. Won't you reconsider?" She looks like she might cry.

I take it from her without looking at it. "I'm sure you'll have a bevy of current and former dancers in attendance. Why do I have to go?"

"It's because of the book. I hope you won't think me insensitive-I mean, I still can't believe what you went through-but the book is the reason they want you there. Everyone is so eager to know more about what happened when you were a Rockette."

Right. A recent nonfiction account of the events of 1956, published a couple of months ago, has stirred up interest in a time I'd rather not dwell on. Since it came out, I've had all kinds of former friends and foes resurface, not to mention reporters who looked up my address and stopped by unannounced, hoping for an interview. It was a time when I was at my best as a dancer, yet the worst happened.

I haven't been in that theater, that beautiful, majestic space, since.

"That was long ago. I don't wish to talk about it. Or think about it."

"Oh." Her eyes flit to the windowsill, where several family photos sit in silver frames. "Of course." She pauses. "I just need to call and let Ms. Burris know. Do you mind if I use your phone?"

I show her into the hallway, where it sits on a narrow table.

As she murmurs into the phone, I go back into the living room, where the young mover has left another box on the coffee table, this one marked with my mother's handwriting. Inside are her treasures, objects that she touched and worried over, pages she leafed through and scribbled on in pencil. I remember the time when, as far as I was concerned, the programs and diaries might as well have been dusted with cyanide.

Piper comes back into the room, tucking a loose strand of hair behind one ear. Her chin trembles. "Ms. Burris is so disappointed. And I'm sorry to have wasted your time. I'll excuse myself now and head back."

Just then, the young mover bounds down the stairs carrying a dress on a hanger across his arms as if it were a sleeping maiden. "Do you want to keep this, Ms. Brooks? Or donate?" He holds the hanger up high to better display it.

"Oh my gosh!" Piper says. "How beautiful!"

It's one of my favorite frocks, sapphire blue with a high neck and long sleeves. I haven't seen it in years, but I know it would still fit.

I wore it one of the last times I saw my first love.

The mover is only doing his job, but I don't want to engage with these questions-or these objects-anymore. The slow drip-drip of memories feels lethal, or at least dangerous enough to drive me from the house. I could stay here and have my heart torn open or I could go into the city and lose myself in the bright lights and the constant swirl of people. I could mix in with the crowd and disappear for a while, and when I return, all this detritus will be gone for good.

I stand there, unsure, and notice that I'm still holding the program in my hand. I open it and quickly scan the run of show: some speeches, a couple of dance performances, a popular singer. And then a familiar name catches my eye. For a minute I'm thrown back to a different time, when I was silly and young and had no idea what the world had in store for me. What suffering, and what bliss.

Well, it appears I have no choice. I take the hanger from the mover and sweep up the fabric with my free hand so it doesn't touch the floor.

"I've changed my mind," I reply. "I'm going after all."

Chapter Two

October 1956

"Dottie, we do not lick the mirror during ballet class, remember?"

Marion dashed to the front of the dance studio, where five-year-old Dottie stood flush against the floor-to-ceiling mirror, fingers splayed against the glass, staring intently at her reflection. Her tiny pink tongue darted out once more before she turned and threw a mischievous smile Marion's way.

"That's enough. Please get back in line with the other girls." Marion took her hand and led her back to her place among the class of ten, clad in pink tights and leotards, with ballet slippers no bigger than parrot tulips on all twenty feet.

Make that nineteen.

Tabitha had taken one shoe off and was batting her neighbor's behind with it.

Marion glanced at the clock. Forty-five more minutes to go. She'd been working as an instructor at the Broadway Ballet and Dance Studio for two years now, after having studied here herself since the age of five. Miss Stanwich, the kindly owner and founder, had asked her to teach the beginners part-time when Marion was a senior in high school, and most days she had a knack for corralling even the feistiest of children. The studio was like her second home, and if anyone asked, she'd say that she enjoyed her job immensely.

Although, to be honest, she'd enjoyed it much more before Miss Stanwich retired and moved to North Carolina. Marion had been asked to stay on by the studio's new owner, Miss Beaumont, who, unfortunately, was difficult to please on the best of days.

Marion put her fingers into her mouth and let out a whistle loud enough that the taxis gliding on Broadway three floors below might have pulled over in hope of a fare. It also served to bring Tabitha's mother to the glass viewing window that connected the studio to the waiting room, where she stood peering with disapproval over her reading glasses, a copy of Woman's Day clutched to her chest.

At the sound of Marion's whistle, all ten girls miraculously fell into place, making two rows of five. Marion signaled for the accompanist to begin playing and led her tiny dancers through another round of pliés.

Copyright © 2023 by Fiona Davis. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.