1

Approaching the museum, ready to hunt, Stéphane Breitwieser clasps hands with his girlfriend, Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus, and together they stroll to the front desk and say hello, a cute couple. Then they purchase two tickets with cash and walk in.

It’s lunchtime, stealing time, on a busy Sunday in Antwerp, Belgium, in February 1997. The couple blends with the tourists at the Rubens House, pointing and nodding at sculptures and oils. Anne-Catherine is tastefully dressed in Chanel and Dior bought in secondhand shops, a big Yves Saint Laurent bag on her shoulder. Breitwieser wears a button-down shirt tucked into stylish pants, topped by an overcoat that’s sized a little too roomy, a Swiss Army knife stashed in a pocket.

The Rubens House is an elegant museum in the former residence of Peter Paul Rubens, the great Flemish painter of the seventeenth century. The couple drifts through the parlor and kitchen and dining room as Breitwieser memorizes the side doors and keeps track of the guards. Several escape routes take shape in his mind. The item they’re hunting is sheltered at the rear of the museum, in a ground-floor gallery with a brass chandelier and soaring windows, some now shuttered to protect the works from the midday sun. Here, mounted atop an ornate wooden dresser, is a plexiglass display box fastened to a sturdy base. Sealed inside the box is an ivory sculpture of Adam and Eve.

Breitwieser had encountered the piece on a solo scouting trip a few weeks earlier and had fallen under its spell—the four-hundred-year-old carving still radiates the inner glow, unique to ivory, that feels to him transcendent. After that trip, he could not stop thinking of the sculpture, dreaming of it, so he has returned to the Rubens House with Anne-Catherine.

All forms of security have a weakness. The flaw with the plexiglass box, he had seen on his scouting visit, is that the upper part can be separated from the base by removing two screws. Tricky screws, sure, difficult to reach at the rear of the box, but just two. The flaw with the security guards is they’re human. They get hungry. Most of the day, Breitwieser had observed, there is a guard in each gallery, watching from a chair. Except at lunchtime, when the chairs wait empty as the security staff rotates shorthanded to eat, while those who remain on duty shift from sitting to patrol, dipping in and out of rooms at a predictable pace.

Tourists are the irritating variables. Even at noon there are too many of them, lingering. The more popular rooms in the museum display paintings by Rubens himself, but these pieces are too large to safely steal or too somberly religious for Breitwieser’s taste. The gallery with Adam and Eve features items Rubens collected during his lifetime, including marble busts of Roman philosophers, a terracotta sculpture of Hercules, and a scattering of Dutch and Italian oil paintings. The ivory itself, by the German carver Georg Petel, was likely received by Rubens as a gift.

As the tourists circle, Breitwieser positions himself in front of an oil painting and assumes an art-gazing stance. Hands on hips, or arms crossed, or chin cupped. His repertoire includes more than a dozen such poses, all meant to connote serene contemplation, even while his heart is revving with excitement and fear. Anne-Catherine hovers near the gallery’s doorway, sometimes standing, sometimes sitting on a bench, always with an air of casual indifference, making sure she has a clear view of the hallway beyond. There are no security cameras in the area. There’s only a scattered handful in the whole museum, and he has noted that each has a proper wire; occasionally, in smaller museums, they’re fake.

A moment soon comes when the couple is alone in the room. The transformation is explosive, a flame to the fuel, as Breitwieser sheds his studious pose and leaps over the security cordon to the wooden dresser. He digs the Swiss Army knife from his pocket, pries open a screwdriver tool, and sets to work on the plexiglass box.

Four turns of the screw, maybe five. The carving to him is a masterpiece, just ten inches tall yet dazzlingly detailed, the first humans gazing at each other as they move to embrace, the serpent coiled around the tree of knowledge behind them, the forbidden fruit picked but not bitten: humanity at the precipice of sin. He hears a soft cough—that’s Anne-Catherine—and vaults away from the dresser, light-footed and fluid, and reassumes art-watching mode as a guard appears. The Swiss Army knife is back in his pocket, though the screwdriver is still extended.

The guard walks into the room and stops, then scans the gallery methodically. Breitwieser contains his breathing. The officer turns around and is barely beneath the doorway before the theft resumes. This is how Breitwieser progresses, in fits and starts, grasshoppering about the gallery, a couple of turns of the screw, then a cough, a couple more, then another.

To unfasten the first screw amid the steady drip of tourists and guards requires ten minutes of concentrated effort, even with the margin for error shaved thin. Breitwieser does not wear gloves, trading fingerprints for dexterity and touch. The second screw is no easier, finally yielding as further visitors arrive, forcing him to bound off again, the pair of screws in his pocket.

Anne-Catherine makes eye contact with him from across the room, and he taps his hand to his heart, signaling that he’s ready for the finishing step and will not need to use her big purse. She heads off to the museum’s exit. The security guard has already appeared three times, and although both he and Anne-Catherine have stationed themselves in different spots at each check-in, Breitwieser is stressed. He’d once worked as a museum guard, soon after graduating from high school, and he understands that while almost no one will detect a detail as tiny as a missing or protruding screw, all decent guards focus on people. To remain in the same room for two consecutive security visits, and then commit a theft, is inadvisable. Three visits is borderline reckless. A fourth, which by his watch is little more than a minute away, must not happen. He needs to act or abandon now.

The problem is the group of visitors present. He slides his eyes over. They’re huddled near a painting, all wearing headphones attached to audio guides. Breitwieser deems them sufficiently distracted. This is the critical instant—one glance from one visitor and his life could effectively end—and he does not delay. It isn’t action, he suspects, that usually lands a thief in prison. It’s hesitation.

Breitwieser steps to the dresser, lifts the plexiglass box from the base, and sets it carefully aside. He grasps the ivory sculpture, sweeps his coattails out of the way, and pushes the work partially into the waistband of his pants at the small of his back, then readjusts the roomy overcoat so the carving is covered. There’s a bit of a lump, but you’d have to be extraordinarily observant to notice.

He leaves the plexiglass box to the side—he does not want to waste precious seconds replacing it—and strides off, moving with calculation but no obvious haste. He understands that such a conspicuous theft will swiftly be spotted, triggering an emergency response. The police will arrive. The museum could be locked down, all visitors searched.

Still, he does not run. Running is for pickpockets and purse thieves. He eases outside the gallery and slinks through a nearby door he’d scouted, one reserved for employees yet neither locked nor alarmed, and emerges in the museum’s central courtyard. He glides over the pale stones and along a vine-covered wall, the sculpture knocking at his back, until he reaches another door and pops through, returning inside the museum close to the main entrance. He continues past the front desk and onto the city streets of Antwerp. Police officers are likely descending, and he consciously keeps his pace easy, shuffling in his shiny loafers until he spots Anne-Catherine and they proceed together to the quiet road where he’d parked the car.

He pops the trunk of the little Opel Tigra, midnight blue, and sets the ivory down. Both of them holding in a bubbling euphoria, he takes the wheel and Anne-Catherine settles into the passenger seat. He wants to gun the engine and screech away, but he knows to drive slowly, pausing at traffic lights on the route out of town. Only when they reach the highway and he hits the accelerator does their vigilance fly away, and then they’re just a pair of twenty-five-year-old kids, joyously speeding, home free.

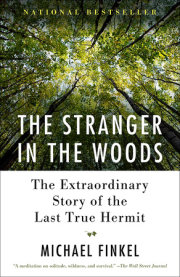

Copyright © 2023 by Michael Finkel. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.