Prologue

I can’t pinpoint the moment I cross over. It comes slowly: the seductive darkness, my face and limbs dissolving into something weightless and fuzzy. Then consciousness spreads through me like caffeine. My senses come alive.

This time there is water. A soft

shhh, on either side of me.

I wait. Try to orient myself. Am I in a boat?

The darkness lifts, and a picture forms. Swamp. I’m in a rowboat, drifting through brown water and swirls of green scum. Around me I see dead leaves, rotted branches curling like fingers, partially submerged trees clawing their way upward. On my right, I catch a flash of movement. Watchful green eyes peer up at me. An alligator.

I drift along, trying to read the light, to get a sense of time. Morning? Evening? The swamp is sunless and dreary, offering no clues.

I feel him before I see him. Someone is with me. A small figure in a white shirt sits across from me in the boat. His face comes to me as if through mist, indistinct smudges giving way to flesh. Is it him? Is it Keegan?

Disappointment stabs me when I see the boy, not quite my son’s age. He’s very small, with skinny limbs. Two, maybe three years old. Pinchable cheeks and longish brown hair.

As if relieved to see me, he smiles, revealing a chipped tooth. I have the feeling that he’s been waiting for me.

Who are you? I ask.

Jo-Jo, he says, as though that should suffice. When he sees my blank stare, he tries to explain.

I lived at the big white house. We had a doggie.

I note his use of the past tense with a frown. Where

are we? I look around for something familiar, something I might recognize, but the swampy land is foreign.

The boy’s smile dissipates, and his eyes search mine.

Will you help me?

He’s so young, his voice still feeling its way around each sentence.

I swallow. Somewhere he has a mother who must love him very much.

How? I ask the boy.

What do you want me to do?

He looks down at his hands, quiet for a moment. The rhythmic swishing of the water engulfs us, an eerie lullaby.

He hurt me, the boy says finally.

You gotta tell on him.

Who hurt you? I press.

If someone’s hurting you, you need to tell your mom.

I can’t! The boy’s voice rises, tearful.

He said no tellin’ or he kill Mama. He kill me, maybe, too.I study his eyes, brown with long lashes, and the dark hair that curls at the tips, just past his chin. I must not forget about the tooth. Front tooth, chipped. Keep every detail intact. I think I understand this vision now, and he’s right, he can’t tell his mother.

He’s already dead.

Par t I

Stamford, Connecticut

O C T O B E R

The sky is a dismal gray when I finally go to remove my son’s car seat. It’s raining, a cold autumn rain that feels both cliché and appropriate for a moment I’ve spent more than three months avoiding. I stand by my Prius, peering through the rear window at the empty booster seat, wondering for the hundredth time about the thin coating of mystery grit Keegan always left behind. And then I do it.

I don’t give myself time to think, just proceed, quickly and efficiently. Loosen the straps. Dig into the cushions of the backseat and unhook the metal latches. One tug, and the car seat lands with a thunk on my driveway.

They never end, all these little ways you have to say good-bye. I turn my face toward the drizzle.

The summer has gone, slipped away without my noticing it, and somehow October is here, flaunting her furious reds and yellows. Squinting, I take in the houses of my neighborhood, their wholesome front yards: trim lawns, beds of waterlogged chrysanthemums, a cou- ple pumpkins on doorsteps. And leaves, of course, everywhere, blazing and brilliant, melting into the slick streets, clogging gutters.

I put my hand to my pocket, feel my keys and wallet. Blink. Try to remember what I’m doing, where I planned to go. Try not to think about the car seat lying behind me in the driveway.

I inhale deeply, wet earth and decaying leaves. It’s Sunday, I remind myself. I’m going to see Grandma. I climb into the driver’s seat and turn on the car, but it all feels wrong. I give myself a minute, wait to see if the anxiety will pass, before conceding that I’ve lost this battle. I can’t drive around town with that gaping void in the backseat. Not today.

Baby steps. One thing at a time.

I exit the car abruptly and head to the garage. Find my bike. It’s Sunday, and I am going to see Grandma. I will stick to the plan. I will hold it together.

Breathe, I tell myself.

Breathe. “Good God, Charlotte, you’re soaking.” Standing in the doorway of her modest apartment, my grandmother looks uncharacteristically rattled.

“I biked.”

Once, Grandma would have been impatient with my running around in the rain, inviting sickness. But life is no longer ordinary. My grandmother’s granite eyes register concern, compassion even, as her gnarled hand waves me inside. I step into the foyer, dripping. Wet strings of hair cling to my forehead and neck.

Grandma peels off my jacket without comment. I can feel her watching, assessing, setting aside her own sadness to make space for mine. It’s a look I first saw when I was fourteen, back when my father died and she took me in. A look that has made an unfortunate resur- gence in recent months.

“There’s a bathrobe somewhere,” Grandma says. “Want a drink? Something hot?”

We are not a demonstrative pair. We are stoic New Englanders who maintain what my ex-husband sarcastically termed “the proper Yankee distance.” Feelings, in the Cates family, are more private than politics or religion. Hot tea, a mug of cocoa—this is the kind of warmth my grandmother has to offer.

“I’m okay, Grandma. I just want to sit down.” To describe myself as “okay” is, of course, a brazen lie. My face tells the story: cracked lips, eyelids puffy from sudden crying spells, skin pale and sickly after a summer spent hidden from the sun.

It’s obvious that I am

not okay, but Grandma says nothing. She puts a hand on my shoulder and gently ushers me into the living room. I assume my usual post on the creaky old rocker while she arranges her- self in a high-backed wooden chair. My grandmother was a beautiful woman in her day, and though she’s lost most of her vanity with age, pride in her good posture has endured.

The living room is, as always, immaculate. Grandma hates knick- knacks. Her bookshelf consists largely of reference materials, although the bottom shelf holds a few guilty pleasures: some Stephen King nov- els,

Cold Crimes magazine (my first steady writing gig), and old issues of

Sophisticate, from before my promotions, back when I was a staff writer. Grandma remains a loyal reader of

Sophisticate, although she isn’t exactly the target demographic for articles like “What You Need to Know About Prenups” and “Preparing Your Baby for an Ivy League Future.”

If my home is one of managed chaos, Grandma’s is one of enforced order. Even my son understood this, and obediently organized his books, games, and art supplies before we left here every Sunday.

“You didn’t have to come, Charlie,” Grandma murmurs. “I know it’s Sunday, but you didn’t have to come.”

“How else would I see you?” My grandmother gets around well for a woman her age, but she no longer drives, and expecting her to navigate the bus system is a little much. “Besides, it’s probably good for me to get out.”

“Did you leave your bike outside?” she asks. “It might rust.” I shrug. “It was Eric’s bike.”

My grandmother’s eyes narrow at the mention of my ex-husband. “Has he called you? Even once, to see how you’re doing?”

There’s venom in her words. She hates Eric with a passion I can no longer muster for his hipster glasses and ever-receding hairline.

The Sperminator, my friend Rae took to calling him after the divorce, aptly summarizing his one lasting contribution to my life.

“Eric and I have nothing to talk about,” I say. “I told him not to call.” I don’t bring up Melissa, his new wife, but my grandmother cannot contain herself.

“I’ll never understand what he sees in that woman.”

My friends made similar comments after the funeral. They all knew she was the Other Woman. I suppose they expected more: good looks, big boobs, animal prints, the kind of trashiness that might have predict- ably turned Eric’s head. But Melissa, like Eric, was unremarkable.

“He did you a favor, really,” my grandmother declares. “You don’t waste caviar on a man who wants corn dogs. She’s exactly what he deserves.”

My whole family was outraged when Eric arrived at our son’s funeral with Melissa in tow.

He has to rub her face in it, I overheard my aunt Suzie say, and maybe that was true. Maybe, in some childish way, Eric has something to prove. I didn’t care about the wife. I was angry that he showed up at all. Eric had visited Keegan only once since he and Melissa moved to Chicago. What right did he have to fatherly grief?

And still, Melissa comforted him. Held him as if the loss were his.

No, I wanted to tell them both,

that’s MY son.

“You know, she works in waste management,” I inform Grandma, suddenly ready to take what cheap comfort I can.

“That explains why she loves trash,” Grandma mutters.

I manage a wobbly smile. We are Yankees. These are her love words.

Two hours at my grandmother’s house have, more or less, the in- tended effect. When it becomes clear that I don’t want to talk, she fills the silence. She tells me about the small fire her elderly, somewhat senile neighbor started. She comments on a recent article in

Sophisticate, an exposé on Botox that she reacts indignantly to. It all feels familiar. Not normal, exactly, but familiar. A life I vaguely recognize as my own.

I’m picking myself up, preparing for the return to my empty, silent house, when Grandma speaks. “Is there anything I can do for you?”

It’s the closest she has come to acknowledging tragedy, and it chokes me up. I swallow and shake my head. There is nothing she, or anyone else, can do.

“I wanted to ask you . . .” She gathers herself up and I can see her steeling herself, preparing to ask an unpleasant question. “The church across the street is collecting donations. They’re looking for children’s items, and of course, I have all these toys around . . .”

It is an entirely reasonable thing for her to ask, and yet I resent it all the same.

“Did you want to hang on to them?” Grandma asks, sensing resis- tance in my silence. “There’s no hurry.”

“No, no, donate them.” I know the right words, even if I don’t truly feel them. “I’m sure some kid could find a use for all that stuff.”

My grandmother nods and collects my wet coat. I’m halfway out the door and headed for the elevator when she calls after me. “Charlotte?”

I turn.

“Do you dream about him?” It’s an odd question.

“I never dream,” I tell her. “Ever. Do

you dream about him?”

She shakes her head. “Sometimes I wish I did.” She blows me a kiss, a gesture I find unexpectedly tender. “Be careful riding home.”

That night, sprawled across the couch in the dark, I wait for my sleeping pills to kick in. Even before I lost Keegan, I needed pills. Now I need more.

Charlie’s only off switch, Eric used to joke, and it’s true.

My body goes slack. My mind swirls. I’m on my way out.

Mom. From behind me, I swear I can hear Keegan’s voice.

Mommy, are you listening?

I try to sit up, but Ambien is pulling me under, filling my head with nothing.

You have to listen, Mommy. It’s time to start listening.

The last thing I’m aware of is the sweet smell of his shampoo, his curls tickling my face. Then the drugs take me away.

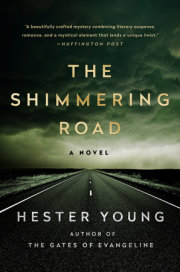

Copyright © 2015 by Hester Young. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.